Beyond Encore: The Recurrence of Gandhi in Textiles

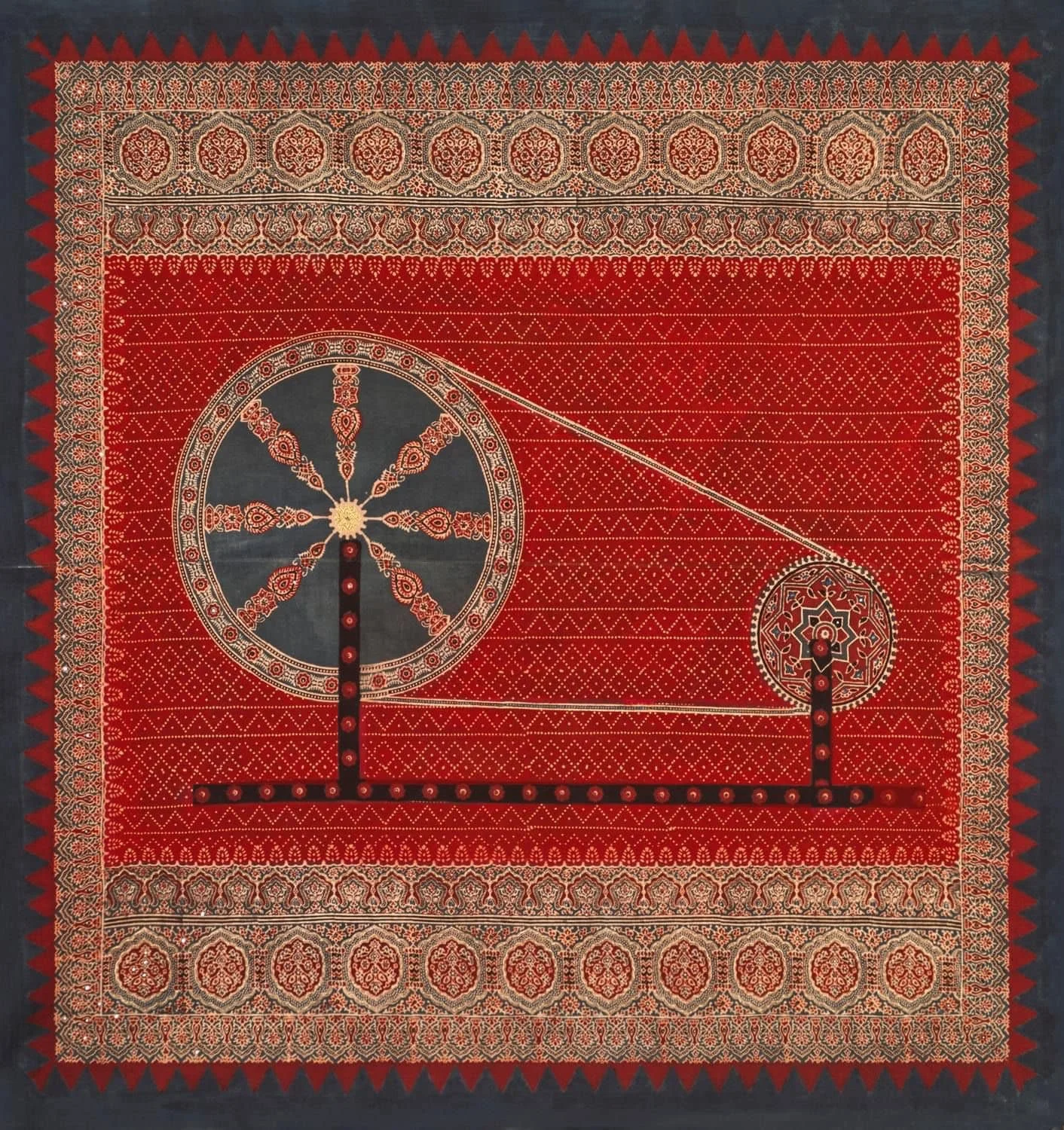

This article was originally published in The Voice of Fashion. Cover image: ‘Charkha—The Wheels of ‘Svavalamban’ (one part of the triptych) by Shelly Jyoti.

Mahatma Gandhi’s legacy is inextricably woven into the fabric of Indian history, and his enduring bond with homemade textile remains indelible. He encouraged Indians to overthrow the British Raj by adopting nonviolence and donning handspun and handwoven khadi. The cloth became a symbol of resistance and self-reliance. Today, khadi is universally synonymous with Gandhi.

When it comes to khadi, Gandhi’s intentions need to be seen in a larger context, says textile curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul. “Gandhi was persuading the elite sections of society to wear khadi, which was very revolutionary. Through this, he hoped for people to give up ‘upper-caste’ associations that they held through cloth, in favour of something that was egalitarian, perhaps a lot like denim today,” he explains.

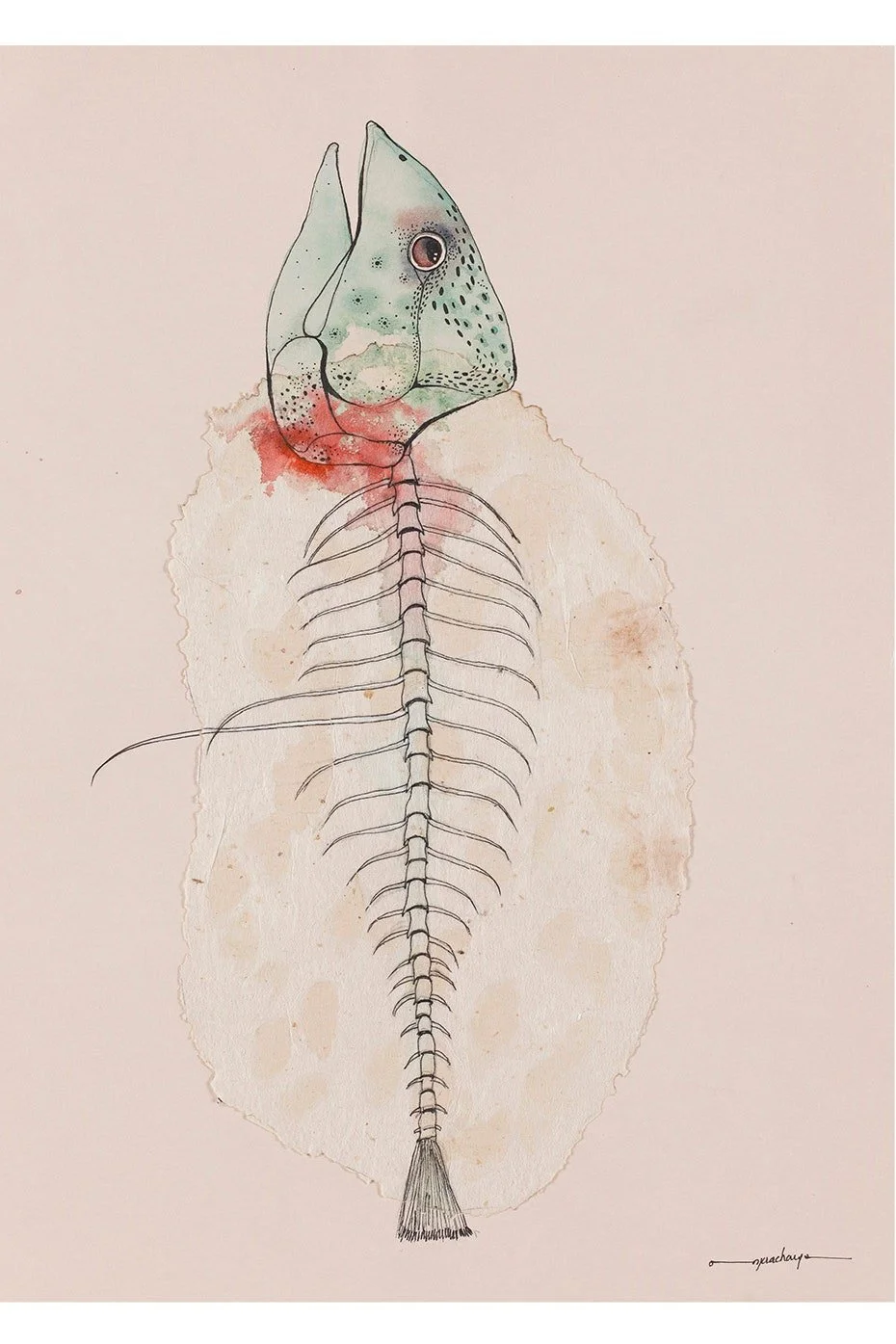

Finding BAAPU by Nupur Saxena.

However, while Gandhi’s push for khadi was well-intentioned, during the nationalist movement, there were murmurs of dissent. Its colour, for instance, became a subject of debate. “There were freedom fighters like Kamala Nehru and Sarojini Naidu, who’ve been documented to be uncomfortable wearing white as this was associated with Hindu widowhood,” says Kaul. “They felt that this was also unfeminine.” But Gandhi was willing to address that. “With him, what was wonderful was that there was room for discussion and debate, even though such aspects of the khadi campaign haven't been highlighted much by historians until recently,” says Kaul.

“There were freedom fighters like Kamala Nehru and Sarojini Naidu, who’ve been documented to be uncomfortable wearing white [khadi] as this was associated with Hindu widowhood. They felt that this was also unfeminine.”

On Gandhi’s 155th birthday, TVOF spotlights some Indian designers and craftspeople who have embraced his multifaceted legacy by presenting him in myriad artistic ways, through khadi and other precious handmade textiles. Through recurring motifs, detailed patterns and distinct colour palettes; through intricate thread-work, block prints and woven retellings—each exquisite textile art is emblematic of India’s treasured heritage and the age-old wisdom of the handmade. It also celebrates Bapu’s immortal presence.

Nupur Saxena’s Sooti Jamdani

Bengaluru-based artist-designer, Nupur Saxena, used sooti (handwoven cotton fabric) as her canvas. Through meticulous techniques of pointillism and halftone used in jamdani weaving, Saxena presented the iconic portrait of Gandhi. The bindu, or the dot, took centrestage. “I always find magic in the most basic elements of techniques in these crafts. Here, I found it in the most used motif of jamdani—the circle. It is usually the first motif a weaver learns on the loom,” says Saxena. “The halftone technique simulates continuous-tone imagery via dots, varying in size and spacing, which create an optical illusion for the human eye to interpret the image as a whole.”

The khadi yarn, which is used for the jamdani weaving in this artwork, “is a metaphor for mindful consumption in Gandhi’s march towards freedom,” she continues. The work, which took three months to make, was in collaboration with master weaver Ratan Biswas from Santipur, West Bengal. At first, Biswas was skeptical about Saxena’s artistic proposal. “When he first saw the design, he said, ‘I cannot see Bapu, but my daughter can, so I’ll trust the process, and weave what you’ve asked for.’ When he finally took it off the loom, he too could see Bapu, and it was the happiest moment for all of us,” says Saxena.

A zoomed in image of ‘Finding BAAPU’ by Nupur Saxena.

The wall art titled ‘Finding BAAPU’ was presented at the Melbourne Museum, Australia and NGMA, Mumbai, as part of Sutr Santati – Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav, an exhibition curated by textiles curator Lavina Baldota in 2022 to celebrate 75 years of India’s independence.

Vankar Shamji Vishram’s Dhabla Weaving

In Kachchh, master weaver and visionary Vankar Shamji Vishram belongs to a family known for multigenerational dhabla weaving and dyeing legacy. He heads the centre, Vankar Vishram Valji Weaving. The tapestry, titled ‘Gandhi’s Dandi March–Salt Tax’ (60 inches x 110 inches), is a stunning piece of labour-intensive dhabla weaving that imaginatively traces Bapu’s Dandi march route.

“To make this work, I read a lot on Gandhiji,” Vishrambhai explains in Hindi. Only geometric designs can be created in dhabla weaving, which limits artistic creativity, yet Vishrambhai wanted to tell Bapu’s story. “I went to Sabarmati Ashram and saw a few photographs for inspiration.” He drew a map where he imagined a meandering route that Gandhiji might have taken towards the coastal town of Dandi when he stepped out of the Sabarmati Ashram. That map was translated into the tapestry, where its indigo border represented the Arabian sea.

Vishram's textile art in kala cotton crafted using the quilting technique of dhabla. Credit: Dastkari Haat Samiti and Google Arts & Culture.

While the traditional dhabla (which means ‘quilt’ among a few communities in Gujarat) weighs between 2 to 2.5 kilograms and is made from sheep wool, for this artwork, Vishram bhai used indigenous kala cotton, natural indigo dye and colours derived from acacia seeds. It took his brother, mother and him almost 50 days to produce the piece. The work was presented at the Cotton Exchange: A Material Response exhibition in 2015, which explored the historical cotton connection between Ahmedabad and Lancashire, UK.

Another important wall art panel at the exhibition depicted the spinning wheel, which is an integral part of the Vankar community. “As children, when we used to get up from sleep, the first thing we saw was the charkha, its bobbin and shuttle. There was no electricity or smart phones in the village back then, so our charkha was our khilona, our toy. It has always been our way of life,” says Vishrambhai.

“As children, when we used to get up from sleep, the first thing we saw was the charkha, its bobbin and shuttle.”

Gaurang Shah’s Khadi Paithanis

Following India’s independence, khadi—the homemade freedom textile—slowly gained a bad rep, often being associated with slow bureaucracy and politicians. Today, however, it has been pulled out of slumber and many designers are using it in interesting ways. For instance, Hyderabad-based textile designer and revivalist Gaurang Shah paid homage to Bapu by recreating 35 glorious paintings woven onto khadi Paithani saris through the jamdani hand-weave. The series, titled ‘Khadi – a Canvas’, was part of the travelling group exhibition 'Santati: Mahatma Gandhi Then. Now. Next', conceptualised by Baldota. It was first presented at NGMA, Mumbai in 2019.

The saris were woven in the village of Alikam, Andhra Pradesh, inspired by select paintings of Raja Ravi Varma. “Gandhiji’s birth date is the same as Ravi Varma’s death anniversary, and while Gandhi is known as the ‘Father of the Nation’, Ravi Varma is considered ‘Father of Modern Indian Art’. So, I have always felt there is a connection between them,” explains Shah. For this project, “over 600 shades of natural dyes were created by hand and 200 kilograms of yarn were dyed.”

Gaurang Shah's khadi sari detail, inspired by the art of Raja Ravi Varma.

Over the course of three years, Shah’s team worked with 40 women weavers in Alikam to create these textile reiterations of Ravi Varma’s paintings. “Each khadi Paithani sari’s pallu, depending on the intricacy of the design, took six months to a year to weave,” he explains.

Shelly Jyoti’s Homage to Indigo Farmers

Since 2008, textile maestro and fashion designer Shelly Jyoti’s oeuvre has been preoccupied with exploring Gandhian philosophies. She’s one of the most recognised designers who has worked extensively on Bapu. ‘Indigo Narratives: Homage to the Indigo Farmers of Champaran, 1917-18’, for instance, is a mesmeric site installation (2009), where Jyoti suspends 300 khadi discs which are patterned by ajrakh block-printing and indigo dye.

They represent and echo the “voices of farmers who died unsung and unheard” while they were grievously exploited during the colonial rule to cultivate indigo, explains Jyoti. The discs are interconnected indicating how each farmer, the generations that followed him, and his community, were subjected to oppression. “The Champaran Satyagraha (1917) was the first nonviolent protest led by Gandhi in India against the British, where he fought for the farmers,” says Jyoti.

A glimpse at Shelly Jyoti's ‘Indigo Narratives: Homage to the Indigo Farmers of Champaran, 1917-18’.

In 2022, she was commissioned by Dastkari Haat Samiti’s founder, Jaya Jaitly, to create a triptych titled ‘Charkha—The Wheels of ‘Svavalamban’, for the New Parliament House in Delhi. Jyoti worked with ajrakh karigars from Bhuj to visually represent the themes of self-sufficiency and freedom, gesturing towards the Swadeshi Movement and Gandhi’s encouragement to boycott foreign goods. Using wooden blocks with 300 to 400-year-old patterns, the symbol of the spinning wheel was created on khadi, which was detailed with elegant mirror work and zardozi embroidery.

While such works showcase the wealth of generational techniques, materiality and imagination of our country, they also spearhead dialogues on slow consumerism and sustainability. As Saxena explains, “Gandhi’s values continue to inspire generations; they directly address pressing contemporary issues like inequality and environmental sustainability. If this isn’t the perfect fodder for creative interpretation, then what is?”