Are Artists from the 1970s still relevant today?

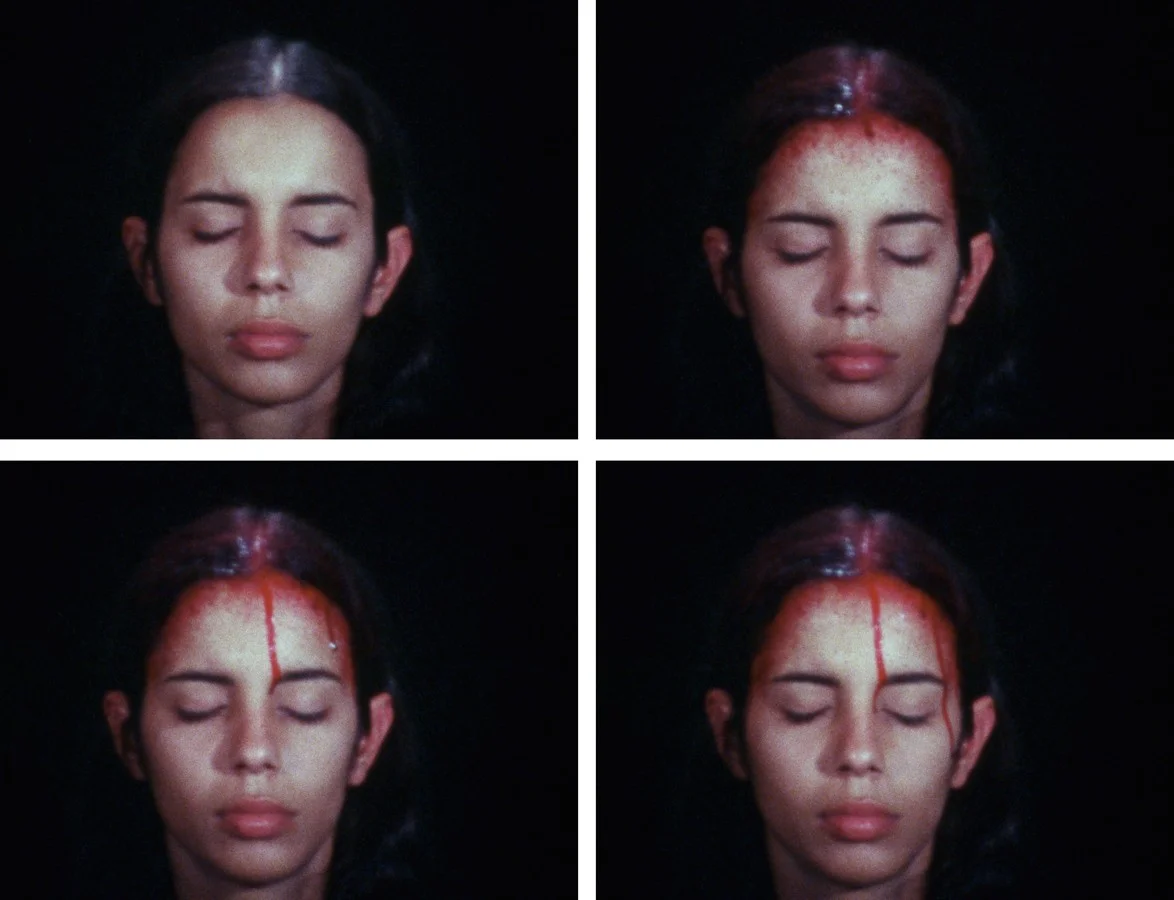

Above: Ana Mendieta's work titled Sweating Blood, 1973. Image Courtesy: Galerie Lelong.

One may wonder why art galleries like Galerie Lelong in Chelsea, New York would be revisiting Ana Mendieta’s body of work—a firebrand of an artist who was slowly becoming popular in the artistic sphere for her peculiar and provocative mixed-media work in the 1970s, before she died a mysterious and unfortunate death in 1985. The artist's exhibition of archival work titled Ana Mendiata: Experimental and Interactive Films is on till March 26, 2016

Mendieta was a bold female artist from Cuba whose works were steeped in feminism. Her repository of films and images was replete with messages and motifs which were way ahead of their time. For instance, she used her body as a canvas across which she splattered animal blood in order to react to the rape and murder of a student. After decades however, why would a handful of art galleries want to resurrect Mendieta’s artwork by showcasing some of her never-seen-before films that are now digitized?

Here’s why: Ana Mendieta’s works have a contemporary relevance, particularly in light of the escalating refugee crisis. Many countries in Europe as well as the United States have argued and debated incessantly over the deluge of refugees spilling onto their shores, but the plight of a refugee—the feeling of being uprooted from his/her country—is seldom thought about or included in mainstream conversations.

But much of Mendieta’s work (who was a refugee herself) is rooted in this sense of displacement. When Fidel Castro’s regime came to power in Cuba, it brought about a political seismic shift that led to the establishment of a Marxist system. Mendieta and her sister were sent to the United States from Cuba by their parents, who stayed behind. She was 12 and her sister was 14. Mendieta used her work as an apparatus to convey the painful and debilitating sense of being lost. Her photographic visual narratives were anchored in the idea of being torn out of the womb of her motherland and thrown into an alien land.

In her Silueta Series, for example, one finds her merged, almost entangled, like roots of a trees with the earth. She termed the series “earth-body” art. Mendieta used her naked body as a canvas, which she covered with leaves, glass, mud, flowers, and even chicken feathers. Many of her silhouette series, rebellious and peculiarly controversial in nature, echoed a ritualistic, almost tribal tradition, which possibly rooted back to her native Cuban heritage. In one photograph, for example, she presses her body (covered in layers of mud) against the bark of a tree, as though intending to be one with Mother Nature.

A feminist, most of Mendieta’s works were politically charged. She used her art to not only explore and celebrate feminine beauty and nature, but also as an instrument to discuss, engage in dialogue, and debate about sexual violence against women. The rape and murder of Sarah Ann Ottens, a nursing student at the University of Iowa where Mendieta was studying Art in the 1970s, had spun a morass of controversies. Mendieta made a film titled the Moffitt Building Piece in 1973.

For the Moffitt Building Piece, Mendieta created a puddle of animal blood and rags across a pavement outside a building. She made it appear as though the blood was seeping onto the pavement from underneath the door of the building. The video, filmed voyeuristically from the window of a car, depicts pedestrians walking on the pavement. They notice the blood streaked across the gravel, pause momentarily, and then continue to walk. The only time the blood (now dried and rust brown) arrests the attention of a woman passer-by is when she returns to the spot and paws at the mush with the end of her umbrella. Disgusted and confused, she turns away and walks off.

None of the passersby knocked on the door of the building or called the police to investigate. The film was used as a medium to convey the lack of concern evident in the people, and to express her frustration with the deep-seated level of indifference in society’s collective consciousness.

Prior to the film, Mendieta constructed a series called Glass on Body Imprints (1972) that externalized her thoughts on how society views a woman’s body. Mendieta used her body as a symbol to demonstrate women being subjected to repression. Though this series is not a part of the current exhibition at Galerie Lelong, it echoes the theme of sexual violence that pulsates dramatically through Mendieta works. In the series, Mendieta presses parts of her body against a transparent sheet of glass where the definitions of her nose, lips, chin, breasts and buttocks collapse, flatten or come together to form a featureless, deformed lump. It expresses how a woman’s body is left in a disfigured state—she loses her identity. Mendieta explores the language of the oppression and exploitation of women, using her body as an instrument that challenges/presses against society.

This fragmentation of a woman’s identity is visually and textually explored and splattered across the walls FLAG Art Foundation’s gallery in Chelsea in the form of a thousand nugget-sized paintings by artist Betty Tompkins. Tompkins is another artist from the 1970s who also rose to fame for her sexually-explicit hyper-real paintings called Fuck Paintings. Her current exhibition titled Women Words, Phrases and Stories, is a poppy, polyglot, multi-colored assemblage of 1,000 textual paintings on canvas.

For this artwork, Tompkins had crowd-sourced the texts by circulating an email that invited people to send in words which they thought best described or were associated with women. The artist received a deluge of 3,500 words, from which she culled 1,000 to make a collage of texts that illustrated a woman’s identity and place in contemporary society. These words are a heady mix of endearment and sexualized, demeaning objectification. While some say: "beautiful", "empowered", "loving", mostly of the words/phrases are highly derogatory -- they range from “vixen” and “slut” to “kept”, “used” and “a sight for sore eyes”.

There are texts like “pussy”, where the artist has painted a black-and-white vulva in soft-focus as its background. Some words’ backdrops are liquid smears of paint, sprays and drips which suggest ejaculatory motion. Canvases with words such as “aggressive” and “hippocrocdogapig” are marked with angry incisions, possibly suggesting a woman’s propensity to be catty, scratch or be violent.

While Mendieta’s work examined the place of women in society in the ‘70s, Tompkins’ recent exhibition reiterates the complexities of it. As a society, has our perception of women evolved? Have we progressed? The works of the two artists currently on display can be considered as articulate responses to those questions. Certainly then, artists from the 1970s like Mendieta and Tompkins are still relevant today.