The Inheritance of War

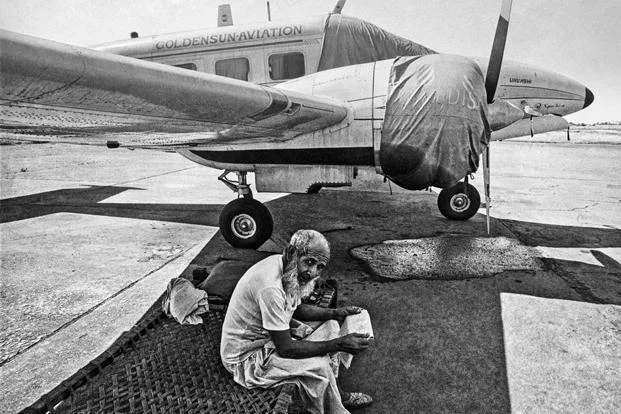

This story was originally written for Columbia Journalism School's Arts and Culture Beat website. Above: A photograph from Rola Khayyat's “BEYroute” series.

Not only sound, but images too can break silence. For decades, visually compelling photographs, although wordless and still, have pierced through the silences shrouding sensitive issues to create an impact.

Rola Khayyat is in the middle of describing the history of the Lebanese Civil War, a 15-year-long, dark period from 1975 to 1990 that left the country broken, bloodied, and scarred. “The history of the Civil War finds no mention in the school textbooks in Lebanon,” Rola tells me. Her voice is excited, almost quavering with anger. It’s a cold, sunless winter morning, and we are seated at the table in her living room in a comfortable Upper West Side apartment in New York. On her wall, hangs a framed 1982 Time magazine cover that reads “Destroying Beirut.”

Rola’s eyes—light brown, alert and expressive—hold me with an intense gaze. “Because there is this silly belief that if it is mentioned, it might inspire another war," she says. "Post-war Lebanon is very much about living with amnesia. I've taken it upon myself to piece together the spliced up fragments of Lebanese history, and the narratives of the silenced or silent majorities.”

A photographer from Lebanon now studying in the Graduate School of the Arts at Columbia University, Rola grew up during the 1980s, when the Civil War was at its peak. Her formative years have been singed with experiences of the war. Themes of memory, identity and war weave into the fabric of her photographic narrative. During the war, approximately 17,000 civilians forcibly went missing. The Lebanese government kept no record of this mass erasure, brushing it underneath the carpet as though it never occurred. Today, it exists like ragged remnants of collective memory living in the minds of those who lost their loved ones.

Now a second-year MFA candidate at Columbia, Rola wanted to resurrect the memory of the missing for her first-year show. Laqqam, one of her most powerful works, emerged from this wish. For the exhibition, she culled sepia-toned archival photographs from an online repository called, Act for the Disappeared that posts photographs of the victims collected from their families. These photographs were then screen-printed on traditional Arabic flatbread and stacked one on top of the other on a belt of beige colored burlap. The installation, in the view of Patrice Helmar, a photographer and friend who attended the exhibition, was “haunting and beautiful at the same time.” It reminded her of a “haphazard grave.”

Laqqam is a word with poetic resonance in Arabic. It means “cutting the bread into pieces,” conjuring in this case an imagery of bodies mercilessly being cut, slit wide open. But Rola’s motivations behind using bread as her canvas are more layered. “I chose bread, because I was thinking about the one thing that unites people about their memory of the Civil War. Arabic bread was an item you’d find common in every household. During the war not many people left their homes, but when they did, it was to get bread from the bakery nearby. So those areas became killing zones for snipers. They targeted people who walked from their homes to the bakeries.”

Bread then becomes an important symbol. Its fragility—the way it can crumble and fall apart—echoes the transience of human life, corroborated by the ephemerality of old photographs and collective memory. As such, Laqqam is reminiscent of Christian Boltanski’s Lessons of Darkness, according to Dr. Aissa Deebi, a visual artist who currently chairs the Department of Art & Design at Montclair State University. “Boltanski dealt with the Holocaust by bringing back personal stories into the public space, and they became a part of art history,” Deebi notes. “Rola is doing something similar in terms of her relationship with her country and the horrible history of Lebanese Civil War.”

According to Deebi, Rola belongs to an emerging tribe of Lebanese artists who have grappled or engaged with the narrative of the Civil War. Like relentless scalpels, artists such as Walid Raad and Walid Sadek have attempted to cut away layers of the anatomy of fabricated history, so how it was conceived, created, circulated, and received can be considered. “There is a whole genre in Lebanese art called Post Civil War that many artists who are interested in it, focus on,” Deebi says. “What’s unique about this phenomenon is that it has been responsible for bringing out the most conceptual work dealing with art and politics in the last 25 years.”

* * *

Imagine growing up in a landscape punctuated by the cacophony of deafening bombs, the nerve-wrecking staccato of guns and the whirring sound of military tanks. As a child, how does one register that; how does one make sense of it; how does one internalize it and cope with it?

Rola’s mother, Fadia Basrawi, made Herculean efforts to shield her five children from the war. Having a vocational background in Child Education, Fadia determinedly carved out a creativity hour in the day where the children had to draw and paint. “She wanted to see whether we were getting disturbed by the war,” Rola says. “As it turns out, we were.”

It was during these hours that Rola’s artistic side began to take shape. Rola spent evenings with her siblings exploring the sprawling, fertile landscape of her imagination and merging it with snippets of war, drawing portraits of a broken city from the eyes of a child. “There are a series of our drawings which my mom has saved, where we’ve drawn army men on tanks with blood on them or expressed wishful thinking (sic) of the Lebanese army triumphing over the Israeli army.”

It was her mother’s preoccupation with photography however, that informed Rola’s artistic vocabulary. “We always had cameras lying around in the house. As a photographer, my mom used to photograph us all the time.” Rola lifts her petite frame from her chair to retrieve a slim cardboard box, which I soon learn, treasures a handful of glossy colored photographs. Their waxy sheen suggests that they were developed during the ‘80s. She rummages through the box, pausing occasionally to pull out a selective few and briefly narrating an anecdote about them. The author of these images is Rola’s mother. Her mother, I imagine, photographed everything—from photographing the birthday celebrations, to documenting her children pitch makeshift checkpoints on the streets, mimicking the Lebanese militia armed with toy guns, halting cars in jest to ask for identification papers.

Initially, it was painting that interested Rola. She packed her bags to receive training at the Florence Academy of Art in order to “find a way of depicting my experiences”. There, she studied classical realist art. She later enrolled in an eight-month long program in Contemporary Arts at Metafora, Barcelona. However, it was an intensive photography program in the summer of 2012 at the Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna that motivated Rola to start over and reconsider her vocational calling. At the Academy, Rola worked closely with South African photographer, Jo Ractliffe whose work deals with conflict photography. Ractliffe’s work examines the aftermath of apartheid in South Africa and documents the landscapes that had been affected by the Angolan Civil War. However, she approaches it in a way that doesn’t show the destruction. They are not grotesque, gory images of war and apartheid, but more nuanced, quiet photographs with subtle imagery.

For the application to the Salzburg program, Rola had sent in her work titled “Beirut.” At some point after the 2006 war in Lebanon (she cannot remember the exact year), Rola picked up the camera and began documenting the streets of Beirut. It was as an unhurried exploration and a means of keeping a record—of preserving the memory of the aftermath of war, before it was erased completely. Weathered, bullet-ridden walls; buildings sized down to rubbles; religious symbols juxtaposed with militia monograms against blood-red bricks inhabited her frames—functioning as indelible reminders of a city that had been flayed alive. “I got into photography because it was a way of helping me to orient myself with my city,” Rola says, meditatively pulling strands of her wavy auburn hair as she tries to articulate her motivations behind her process of picture-making. She pauses idiosyncratically between words, as though extremely mindful of the sentences she constructs.

From the “BEYroute” series. Photograph by Rola Khayyat

Rola’s photographs functioned as a reaction to the blanket of amnesia that settled over Lebanon post the war. “The war ended, and people immediately wanted to move on. Even the façade of the city changed drastically. Bombed out buildings were being reconstructed and repainted.” She opens a photograph on her laptop that she made. It’s an image of a pale, blue wall that has been haphazardly smeared in white paint. In the middle of the frame is an unassuming black-and-white passport photograph glued to the wall. In the winding gullies of Beirut, you’d find such photographs stuck to walls, which are images of those who’ve either gone missing or have died. “Whenever anybody dies, they put a poster on the walls to inform everybody; the posters inform you where you can pay your respects.” The streets then become public obituaries.

One of the most poignant photographs is the image of a young boy, with his back facing the camera, curiously reaching out on his toes, to touch the graffiti of a bomb painted on a faded, pastel yellow wall. In another corner, there is a faintly painted symbol of the religious cross in red. It’s a beautifully captured, telling moment isolated in time. While childhood is often associated with innocence and happiness, this photograph underscores the debilitating gravity of war. Not all childhoods are pleasant and fancy-free.

For Patrice Helmar, this is one of the most captivating photos from the series. “Rola is a poet,” she notes. “She’s lyrical in her photographs. She’s not interested in shocking you with images of war, but gently nudging the viewers to look at the symbolic reminders of what it means.” Rola credits this language of subtle storytelling to Ractliffe. It was Ractliffe’s work that pushed her to apply to the MFA program in Photography.

* * *

Couched in Rola’s work is the exploration of collective memory, and a desire to piece together the Lebanese history. To map the history, the story of the Lebanese Jews is important as well. Before the Civil War, there was a thriving community that was integrated seamlessly into the fabric of Lebanese society. “Back then, it was like one big family,” Rola says. "My grandmother had fond memories of Jewish neighbors and co-habitation.” While some Jews began leaving Lebanon after Israel came into being in 1948; others left in the ‘60s. However, it was the growing internal strife between the Christians and Muslim Arabs in the ‘70s that disrupted the remaining Jewish quarters like a hurricane, scattering thousands into neighboring lands. Today, only a handful remains in the country, existing at the fringes.

Synagogue in Bhamdoun. Photograph by Rola Khayyat

Researching for her final year thesis that is still in its embryonic stage, Rola visited her homeland and photographed the desolated, destroyed cemeteries and synagogues in Bhamdoun and Saida (Sidon)—forgotten landmarks of a community that has been almost been historically wiped out. By photographing these last vestiges, the attempt is to resurrect the past, to immortalize these monuments through photography, before their complete obliteration.

I meet Rola at her studio tucked within the Watson Hall on Upper West Side. Dressed in a knitted, boat-neck beige sweater and faded jeans, she leads me to a small room with white walls. In a corner of her studio, is a shelf filled with books with titles such as, “Geography and Memory” and “Frames of War.” Taped to the walls are black and white prints of the synagogues and cemeteries that come together in a beautiful, unintended collage. The photographs are quiet visual narratives, minimalist in aesthetic intent. Placing my hands behind by back, I tour the space, trying to read her monochromatic images. Rola’s eyes follow me, noting the path of my movement, my expression, my gestures. It feels as though she’s trying to imprint a vision in her memory, even though she’s not holding a camera, she’s making a photograph in her mind.

The first picture is of a synagogue in Bhamdoun—the largest one in Lebanon that now stands forsaken. It features The Holy Ark, where the Torah (a sacred, hand-written scroll that contains the text of the Five Books of Moses) was once kept. Across the synagogue’s aging, discolored walls, a band of light falls gently. It is in that moment, in that afternoon glow, that Rola succeeds in capturing a fleeting glimpse of the majesty the synagogue once exuded.

Another photograph features a cemetery in Saida. In the foreground, an animal skull sits at the crown of a grave. The grave’s marble surface has been stolen by raiders. Animal bones lie scattered across, because a neighboring slaughter house uses the site as a dumping ground. It’s disconcerting to see a burial site disrespected to such a degree, and it speaks volumes of how the Jewish community is regarded there.

The cemetery and the synagogues are not accessible to the public. “There is a Jewish community in Brooklyn that’s working with some locals in Lebanon to renovate such spaces. They’ve built a wall around them, locked them up and put up signs that say, ‘Don’t Enter.’” But Rola, whose mother describes her as someone who cannot be argued with when she goes on a “photography mission,” devised an alternative route to enter. “I mean, it’s an abandoned building. If you get scared by a sign, you run away; but if you want to take the risk, you climb the walls. So I climbed the wall.” She explains in a candid, matter-of-fact way.

For her thesis, Rola is documenting the Lebanese Jews of Brooklyn. The community has the largest diaspora in the borough. Rola’s wishes to photograph the interiors of their homes—spaces filled with precious objects that are signifiers of the community. She’s also curious to see their response to the pictures she has made in Lebanon. A few months ago, Rola met Raymond P. Sasson—a middle-aged Lebanese Jew who has been living in Brooklyn since the age of two. According to Rola however, despite having lived his entire life in another land, he is more Lebanese than anyone else she’s met. “He even has the flag of Lebanon as his cover picture on Facebook!” she tells me.

On a cold winter morning, tucking our hands in our pockets and burying our chins deep into our mufflers, we head to Ocean Parkway to meet Raymond. He owns a small, antique silverware shop, few meters away from King’s Highway train station. Inside, the walls hold the sunlight brightly. Skirting these walls are tall wooden cupboards with glass doors that treasure rows of gleaming vintage silverware. Raymond is a charming, amicable personality with eyes the color of marble blue. He talks superfast, one word running to catch the other, as he tells me about his first trip to Lebanon with his mother. “It was an emotional journey for her,” he says, “she hadn’t visited the country since the time of the Civil War.”

Soon, he predictably shifts to talking about the Israel-Palestine conflict. As he segues into an almost uninterrupted monologue, Rola quietly makes her way to Raymond’s work table. Something has caught her eye. She picks up a black-and-white family portrait, and meditatively looks at it. It’s a photograph of Raymond’s family before he was born. Across checkered flooring, a family of eight, poses for the camera. In the foreground, the mother (with hair neatly pinned, wearing a knee-length dress) sits in an old-fashioned chair with her arm around one of her daughters. Behind them stands the father in a black suit, smiling vaguely, with five of the other children.

Rola walks to a round wooden table at the center of the shop. Sunlight pours in through the glass of a grilled door; it draws patterns on the table. She places the family portrait on it. Next to it, she puts Raymond’s silver cup-like cardholder. Rola then bends down to her knees to get to the eye level of the table. Holding the camera near her chest, she waits. She takes her time, as though trying to be one with the space that she inhabits. When Rola’s ready, she begins making pictures. Her entire focus hinges on the two objects before her; it’s as though the world for her has shrunk into the glass of her viewfinder. It’s astonishing to note the degree of attention Rola submits to the subjects. She moves back and forth, switching between cameras (a Nikon F2 and a Canon EOS 7D), and pauses only once, placing both of them down to knot her hair into a loose bun. By the time she’s done photographing, she has spent at least 20 minutes crafting that one frame. Her approach is meditative, quite unlike photographers who point and shoot a series of photos in quick succession.

For this series, Rola is keen on photographing objects—souvenirs, mementos, keepsakes that members of the community in Brooklyn keep and cherish that remind them of Lebanon—anything that stirs within them a memory of what their families once called home. “I want to photograph their spaces and see how they represent Lebanon through the objects they own, and if Lebanon features in their lives in any way.” She then pauses momentarily and purses her lips. “I’m also interested in the Lebanese Jews because, in a way, even though I’m an Arab Sunni, it’s sometimes easier to look at a community that has aspects of your identity, but is also somewhat removed. It’s somewhat like looking in the mirror and learning more about yourself through a familiar, yet unfamiliar group of people. So this experience is very much a self- exploration as well.”

Through her photographic work, Rola is trying to map for herself the history of the war. War is very much part of her identity, and in order to understand her identity better she’s piecing together the narrative of her country, one frame at a time.