The Immortality of Absence

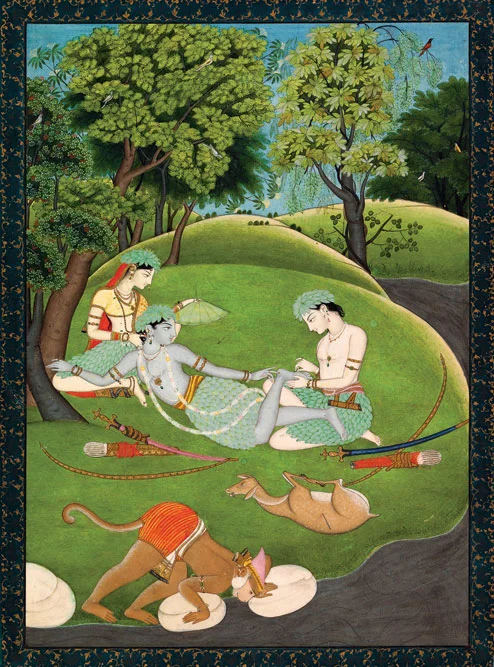

This piece was originally published in Arts Illustrated. The above photograph features ‘Vriksh Nata’ (Arboreal Enactment), 1991–92 by Mrinalini Mukherjee

In June this year, the MET Breuer held Mrinalini Mukherjee’s first retrospective in the United States. It opened to a grand audience, shepherding art connoisseurs, critics, collectors, enthusiasts and writers from across the globe. The retrospective was a token for posterity, in remembrance of a cerebral artist who died well before her time, but produced a wealth of otherworldly sculptures that were sensual and unapologetically unconventional.

Her legendary hemp installations – laboriously knotted into evocative figures and dyed in muted, earthy hues – found a place in the pantheon of Indian art history. Each work carried a reflection of nature or natural surroundings. ‘I think they all have a relationship with the human form,’ Mukherjee told Marjorie Althorpe-Guyton (the former head of Visual Arts at Arts Council England), in an interview in 1993. ‘I think the earlier works maybe started with the idea of a plant or some form of nature, but they sort of took on a human scale and gradually became more human.’

It was in the early 2000s that Shanay Jhaveri, today the Assistant Curator at the MET’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, South Asia, became aware of Mukherjee’s art and its austere beauty. ‘The first work I saw in person was Adi Pushp II (1998 –99) in a private collector’s home,’ Jhaveri wrote to me. ‘I was immediately drawn to the work’s bold evocation of sexuality, the exceptional handling of fibre and the deft deployment of colour.’

In 2016, when he joined the MET as an incumbent curator, Jhaveri immediately proposed the idea of holding a solo exhibition on Mukherjee. However, the artist had passed away a year before that (in 2015), and Jhaveri had set himself up for a challenging task as the curator.

In her absence, the retrospective had to summon Mukherjee’s glowing spectral presence. ‘Curating an artist retrospective in their absence is a daunting and delicate task,’ he admitted. ‘One is tasked with understanding their legacy without having the artist be an interlocutor, present to answer questions. There is a certain responsibility the curator must shoulder in presenting the work as close to the artist’s intention, but strike a balance in exhibiting it with a certain point of view as well.’ There were moments during his research process when Jhaveri would have ‘liked to ask Mukherjee some very specific questions about her materials, working process and aesthetic considerations’, but he had to rely ‘on the memories and reminiscences of friends, interviews and files in her archives.’

In the note that Jhaveri sent, he relayed how Mukherjee resided in the same barasti that was once lived in by artist Nasreen Mohamedi in New Delhi. Mohamedi, a Modern great, had lived a short life too, measured by her fine monochromatic drawings, pocket diaries and a debilitating disease that led to her untimely demise. She died in 1990 at the age of 53. In 2013, Roobina Karode, the Director and Chief Curator of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA), Delhi, decided to pay a tribute to Mohamedi. Once Mohamedi’s student at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, she relied on her vivid memories to curate an extraordinary exhibition on the artist.

As her student, Karode spent numerous evenings at Mohamedi’s studio apartment in Baroda, watching her work at her drafting table below a low-hanging lamp, while Bhimsen Joshi played in the background. ‘She used to sit on a gaddi (small cushion) or a low stool on the ground like a yogi – with her legs folded – and she would draft her line-based abstractions on paper,’ recalls Karode, who was 17 at the time. ‘Nasreen would tell me to do my drawings and sketches, while she did hers. After that, she wouldn’t speak to me at all. She would forget my presence and become totally oblivious to the fact that there was somebody sitting near her.’ It was only later, when Mohamedi would lift her head to take a break and smoke a cigarette that she would acknowledge Karode again.

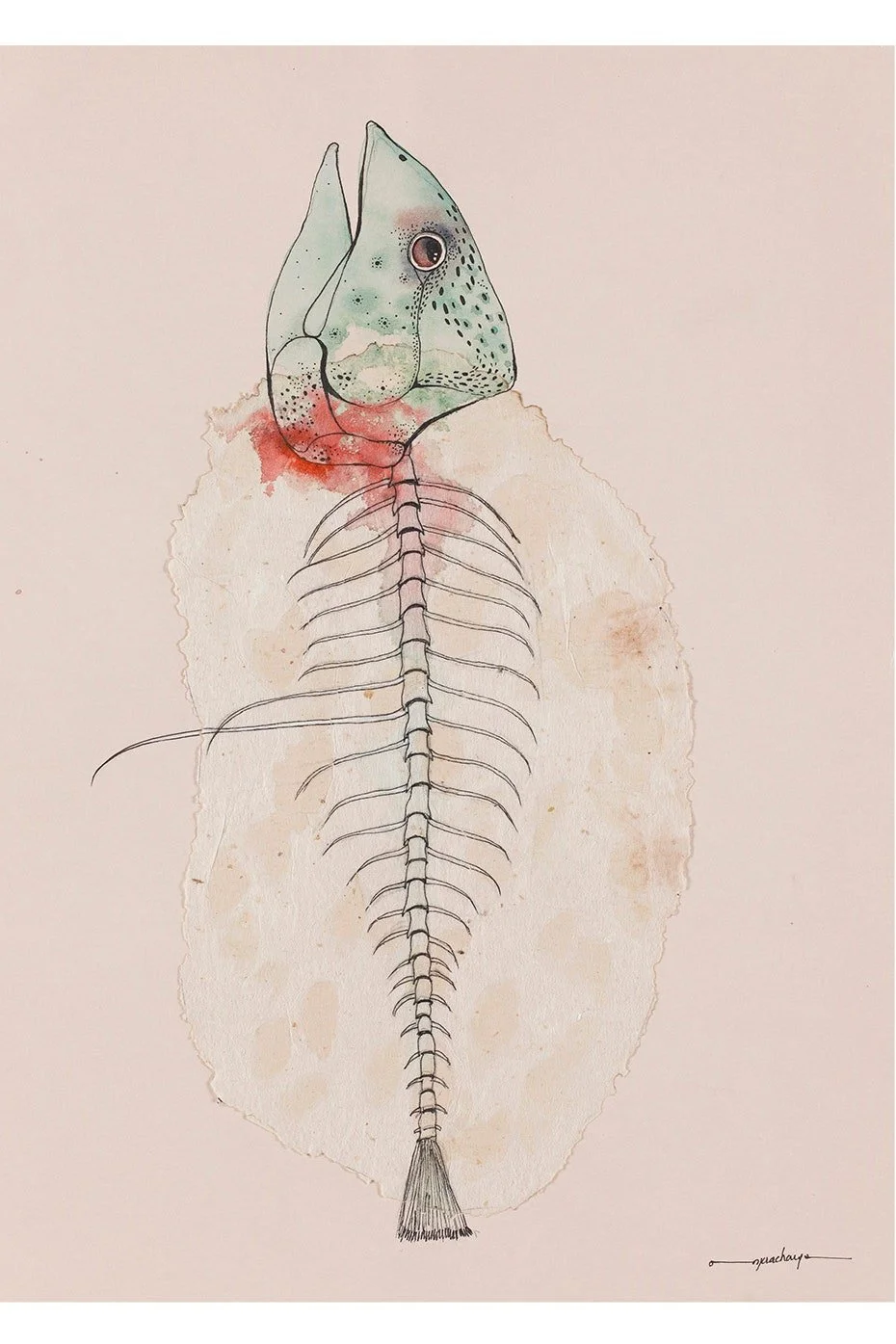

Circa 1980s, ink on paper. By Nasreen Mohamedi. Courtesy: Chatterjee & Lal, Mumbai

Like her drawings, Mohamedi was an artist of few words. For her, the work was a very intrinsic experience. As Karode speaks, she rummages through her memory, recreating a time gone by. It feels as though I am sitting beside Mohamedi, observing her phantom draft finite lines at her Baroda studio in the quiet of the night. It’s a similar experience that Karode created at Mohamedi’s exhibition in 2013. ‘Curating the exhibition was challenging for me. I wanted to reconstruct her essence, I wanted to make her presence come through her absence,’ Karode recounts. ‘She had left impressions on my mind; her memory had lived within me. But I, emotionally and objectively, had to straddle both worlds. However, I had to objectify my curatorial vision.’

Holding exhibitions that map the trajectory of an artist’s career can be an immersive, gripping experience, akin to being momentarily possessed by the artist’s spirit. ‘A lot of people told me that they were moved by the exhibition, because they could feel Nasreen’s presence. So, I think she must have possessed me in some way, because I was so immersed, vacillating between memory and imagination, that it was an overpowering experience,’ says Karode.

Ranjit Hoskote, on the other hand, an art critic and a curator for the past three decades, isn’t necessarily preoccupied with the distinction of living and dead artists. From Jehangir Sabavala to M.F. Husain, he has curated a range of art exhibitions, both in India and abroad. ‘I think in my case, the living artists I’ve worked with have been very respectful of the curatorial mandate, so they’ve never tried to determine the shape or the direction of the art shows,’ he tells me one Saturday afternoon. ‘I’ve done two mid-career retrospectives of Atul Dodiya, for instance, and Shakti Burman, for instance. So, it doesn’t make a difference whether the artist is living or dead.’

Hoskote has had the opportunity of establishing a memorable relationship with veteran painter Jehangir Sabavala in the late 1980s, having first reached out to him as a college student in 1987. ‘I was the editor of our college magazine, and it was the college’s 150th anniversary, I think. So, we went ahead and asked him whether he would give us a painting for the magazine’s cover, and he was very happy to do so.’

Much later in 2006, Hoskote curated Sabavala’s lifetime retrospective at NGMA, in Mumbai and New Delhi. ‘That was a very classical exhibition, it really was also chronological,’ recalls Hoskote. Sabavala passed away in 2011. In 2015, Hoskote was approached by Sabavala’s family to curate another exhibition on the revered artist at Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai, this time in the artist’s absence. ‘Unpacking the Studio was very different from the earlier exhibition,’ admits Hoskote. ‘This was a deeply emotional one. It involved a process of looking at Jehangir’s sketchbooks without him present and it involved presenting a different way of looking at Jehangir and his art.’

The exhibition Hoskote envisioned was laid out in five prominent chapters. In each chapter, Sabavala’s work was contextualised with reference to a milestone that had been very important to his life. ‘One of them was on the Bombay schools that never got looked at – because we all saw him as a product of his education in Paris and London. But here was an opportunity to look at his years at Elphinstone College and Sir JJ School of Art (1944), and present those works. Then there was another chapter on his fascination with monastic life, with Buddhism. So, it was just quite a dramatic re-contextualisation of Jehangir’s work.’ Also on display were an easel and Sabavala’s worn-out painting instruments – his personalised palette, a family of brushes and spatulas.

Do the works of artists who pass away take on a different life, I ask. ‘I think your relationship to them takes on a different life sometimes,’ muses Hoskote. ‘Or sometimes there is more of an archive that becomes available, or your own perceptions shift, it’s difficult to say. But sometimes in hindsight, a whole pattern hits you or the shape of a life that manifests in a way that might not have been before.’