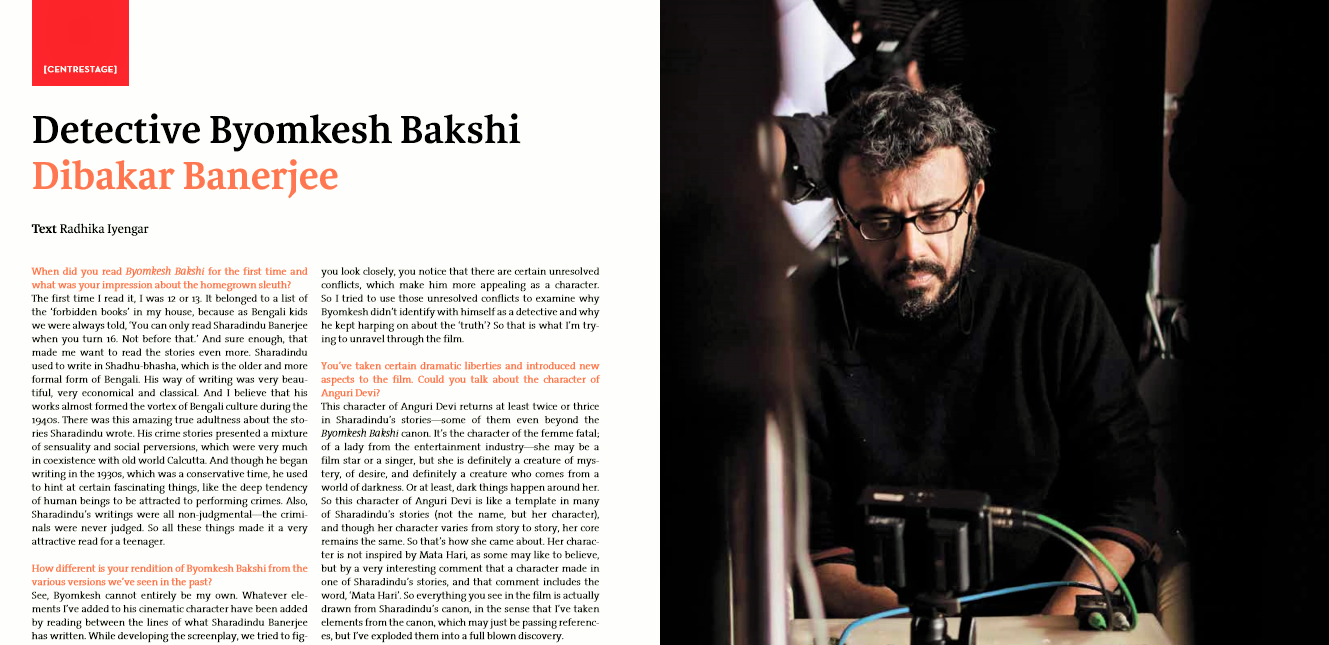

In Conversation with Dibakar Banerjee

Detective Byomkesh Bakshy!

Indie film maker, Dibakar Banerjee returns with a cinematic offering that sees the resurrection of iconic, fictional character without whom the pantheon of Bengali literature would be incomplete: Detective Byomkesh Bakshy. The film the eccentric sleuth celebrated for his impeccable memory and erudite observations, at the beginning of his career. Banerjee talks to me about the film and his childhood obsession with the character.

When did you read Byomkesh Bakshy for the first time and what was your impression about the homegrown sleuth?

The first time I read it, I was 12 or 13. It belonged to a list of the ‘forbidden books’ in my house, because as Bengali kids we were always told, ‘You can only read Sharadindu Banerjee when you turn 16. Not before that.’ And sure enough, that made me want to read the stories even more. Sharadindu used to write in Shadhu-bhasha, which is the older and more formal form of Bengali. His way of writing was very beautiful, very economical and classical. And I believe that his works almost formed the vortex of Bengali culture during the 1940s. There was this amazing true adultness about the stories Sharadindu wrote. His crime stories presented a mixture of sensuality and social perversions, which were very much in coexistence with old world Calcutta. And though he began writing in the 1930s, which was a conservative time, he used to hint at certain fascinating things, like the deep tendency of human beings to be attracted to performing crimes. Also, Sharadindu’s writings were all non-judgmental—the criminals were never judged. So all these things made it a very attractive read for a teenager.

How different is your rendition of Byomkesh Bakshy from the various versions we’ve seen in the past?

See, Byomkesh cannot entirely be my own. Whatever elements I’ve added to his cinematic character have been added by reading between the lines of what Sharadindu Banerjee has written. While developing the screenplay, we tried to figure out why a 24-year-old boy, fresh out of college in 1943, chose to be a detective over the job of a teacher, a doctor or an engineer. Why, in 1943, when jobs were scarce, in a country that was witnessing political turmoil, he chose to neither join the political movement nor lead a middle class life. Instead, he picked a totally reference-less path for himself. He would obviously be a maverick and an idealist. Another thing that interested us was that Byomkesh always referred to himself as the "seeker of truth"; he hated being called a detective although he worked as one. So there was a bit of a dichotomy within him—he was trying to hide from himself a bit. When you look closely, you notice that there are certain unresolved conflicts, which make him more appealing as a character. So I tried to use those unresolved conflicts to examine why Byomkesh didn’t identify with himself as a detective and why he kept harping on about the “truth”? So that is what I’m trying to unravel through the film.

You’ve taken certain dramatic liberties and introduced new aspects to the film. Could you talk about the character of Anguri Devi?

This character of Anguri Devi returns at least twice or thrice in Sharadindu’s stories—some of them even beyond the Byomkesh Bakshy canon. It’s the character of the femme fatal; of a lady from the entertainment industry—she may be a film star or a singer, but she is definitely a creature of mystery, of desire, and definitely a creature who comes from a world of darkness. Or at least, dark things happen around her. So this character of Anguri Devi is like a template in many of Sharadindu’s stories (not the name, but her character), and though her character varies from story to story, her core remains the same. So that’s how she came about. Her character is not inspired by Mata Hari, as some may like to believe, but by a very interesting comment that a character made in one of Sharadindu’s stories, and that comment includes the word, ‘Mata Hari’. So everything you see in the film is actually drawn from Sharadindu’s canon, in the sense that I’ve taken elements from the canon, which may just be passing references, but I’ve exploded them into a full blown discovery.

What went into recreating Calcutta in 1943?

It took us one-and-a-half years of research. Our production designer spent about 3-4 months in Calcutta where she collected the usual research material by going to museums and libraries, as well as collecting recordings of oral histories. We talked to a lot of octogenarians and a few nonagenarians about life in the early ‘40s. That information, specifically, gave me a moving picture of Calcutta back in the day because it’s not only about the architecture, the vintage cars and homes. It’s about the life on the streets, the sounds in the city; it’s about minor details like the style of the zebra crossing at the time or the sounds of the hawkers’ calls. If you were to walk in the heart of Calcutta at six in the morning, chances were that the streets would be cleaned by a tram running on a track, with a hose connected to it. The water would arc about 40 feet across the road and there would be pedestrians nonchalantly walking below the arc, because they knew that it would never fall on them.

Now, these details you cannot get from doing research in the museums. These details you get from the books and the memoirs written at that time (like Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s memoirs and Tapan Raychaudhuri’s Bangalnama). We also saw a lot of films, which were made in the ’30s and ‘40s. We found a fantastic gem—a B-grade movie made in 1931 called Jamaibabu which was shot candidly on the streets of Calcutta, and that gave us a lot of detail about the street culture. In addition to that, 1943 was when Japan was bombing Calcutta, so we spoke to a lot of English people who were living in Calcutta at that time. We unearthed their memories of the war, the sounds of the bombs and so on. And then we started reconstructing it bit by bit.

Reinventing a classic is not new, but adaptation is not an easy thing. How did you adapt a Bengali text into a Hindi language script, ensuring that there was nothing lost in translation?

Urmi [Juvekar] and I wrote the screenplay while I penned the dialogues. It’s not possible to completely transmit Sharadindu’s economical, dry, classical Bangla into the screenplay. Which is why when [Stanley] Kubrick adapted [William] Thackeray’s novel Barry Lyndon, he used Thackeray’s language as the base, and then he went on to create a cinematic language, which was in tempo with Thackeray’s writing.

One of our early adaptations had Ajit’s voice-over. It was working as a script, but it was not working as a concept because we realized that we were again looking at Byomkesh through Ajit. I wanted the audience to have a direct contact with Byomkesh. So we took the spirit of adventure and the energy of the language in Sharadindu’s stories. There was a certain way that the locals used to talk in the 1940s. At this time, since the people read Bengali and English, they could rarely speak in one language. That happens today as well, where, as average Indians we can neither express ourselves completely in Hindi or in English. So I did not want to go into translating the Bengali language—that would be a futile effort, but I wanted to focus on the cadence and the ease with which a Bengali spoke. In addition to that, the youth of 1943 Calcutta was fairly anglicized. So the language of Byomkesh Bakshy is a strange mix of easy Hindi and contemporary debased English. As a result, you keep forgetting whether you are in 1943 or 2014, which is what I wanted.