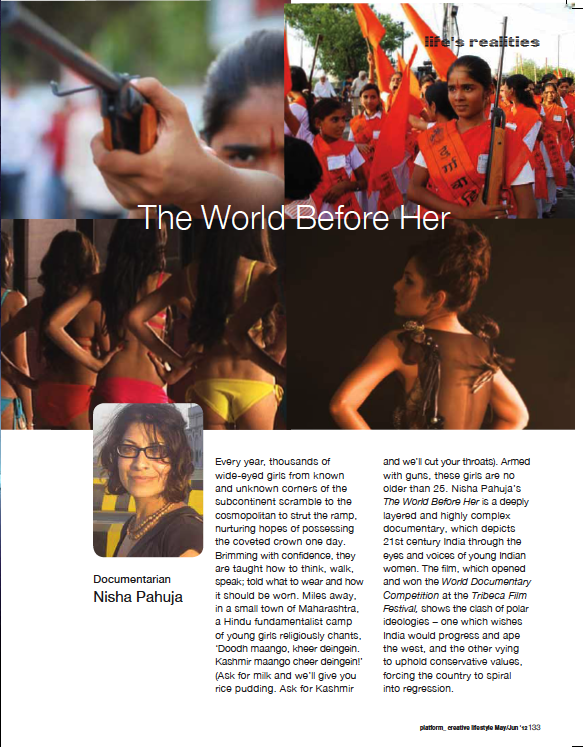

Nisha Pahuja's The World Before Her

Every year, thousands of wide-eyed girls from known and unknown corners of the subcontinent scramble to the cosmopolitan to strut the ramp, nurturing hopes of possessing the coveted crown one day. Brimming with confidence, they are taught how to think, walk, speak; told what to wear and how it should be worn. Miles away, in a small town of Maharashtra, a Hindu fundamentalist camp of young girls religiously chant, "Doodh maango, kheer deingein. Kashmir maango cheer deingein!" (Ask for milk and we’ll give you rice pudding. Ask for Kashmir and we’ll cut your throats).

Armed with guns, these girls are no older than 25. Nisha Pahuja’s The World Before Her is a deeply layered and highly complex documentary, which depicts 21st century India through the eyes and voices of young Indian women. The film, which opened and won the World Documentary Competition at the Tribeca Film Festival, shows the clash of polar ideologies – one which wishes India would progress and ape the west, and the other vying to uphold conservative values, forcing the country to spiral into regression.

What drew you towards depicting the lives of young women in India, particularly through interweaving two diametrically opposite ideologies?

Originally the film was supposed to be about the Miss India pageant as a way to look at modern day India – as a country in transition. I wanted to understand how women were being used to shape this new India and were themselves also shaping their new post-liberalization country. The fundamentalist angle was really supposed to be the voice of opposition both vis-à-vis the growing westernization of India and as a representation of patriarchy. But then, I met Prachi (a Durga Vahini camp leader), and she told me about these fundamentalist camps. The Durga Vahini camps themselves have their vision of what both India and the Indian women should be. And I realized at that point that if I could get access to these camps, I’d have a film where I could explore the crossroads where I feel India is at right now, and how that larger national conflict is playing itself out on the bodies of women. Women and nationalism – it’s an old, global story and it’s taking place right now in a country poised to become one of the most powerful nations in the world.

A still from the documentary

Of Indian origin and residing in Canada, how much do you feel an insider-outsider perspective has helped shaped your film?

It’s interesting because even though I’m an NRI, I have been coming to India since 1999. And it is because I’ve spent so much time in India and because I speak Hindi, that I have been able to get access to different worlds and people within India in a way that foreign filmmakers don’t. They wouldn’t be able to perhaps gain that level of trust, that level of intimacy that I am able to achieve, and that has a lot to do with me being from here originally. At the same time, because I’m also an outsider, I can in some ways see and observe things that other people who are from here don’t necessarily notice. For instance, for me the most dramatic illustration of that while making the film was when the beauty pageant contestants were walking the ramp on a beach in Goa and were told to wear cloth bags over their heads.

Marc (Robinson) who at that point of time had to judge the girl who had the most beautiful set of legs was just doing his job. And for him the best way to do the job was to cover these women and have them parade around in cloth bags so that he wasn’t distracted by the beauty of their faces. So here, their identities were completely obliterated and all you saw were legs! And my crew and I were stunned, but nobody else involved in the pageant, neither the organizers nor the contestants, nobody thought this was offensive, ironic or problematic. None of the girls protested. Whereas for me, the connotations as a westerner were so profound! It was a complete annihilation of a woman’s identity.

A still from the documentary

Beauty pageants and the fundamentalist camp for girls, are both platforms which seem to empower women in their own way, but also play into the patriarchal interests and demands of society. How did you manage to draw parallels between the two dichotomous groups?

What a very smart observation and I hope others pick up on it. Yes, they are in their own curious ways, empowering yet these roles have been defined and dictated by men. For the pageant contestants, you can be wealthy and famous but you have to look a certain way, talk a certain way, because ultimately you will help to feed a capitalist system that is dominated and controlled primarily by men.

The Durga Vahini girls on the other hand, are encouraged to become ‘warriors’, but they must also continue the growth of the Hindu nation beyond all else. What I found very curious, especially with the Durga Vahini girls was how they managed not to be confused by the mixed messages they were getting – to be strong and subservient at the same time. I questioned them, but none of them understood my question. Clearly, they did not see the contradiction. As for me drawing parallels – I didn’t. The parallels simply existed because that is the nature of both worlds – both worlds were about two different ideologies, but the goal of each was the same. All my team and I had to do was capture the processes as they unfolded and the parallels became clear.

While scripting and filming, what vantage point did you position yourself at and how challenging was it for you?

It’s interesting because for me, I didn’t necessarily take sides. For me, it was really about observing and capturing reality and things as they were unfolding. And as much as possible I wanted to try and get the girls take on what was happening. Of course, I had thoughts and opinions but sometimes I feel that one’s opinions aren’t as important as what people are telling you. That it is more important to observe and understand what people are saying.

And I did express my opinions a lot, especially with the fundamentalists – especially with Prachi and her father. I certainly did challenge them and they certainly knew what my perspective was. I made it very clear that I didn’t buy into their politics, and the way they thought about women and the things that they wanted – but I really wanted to understand why they felt the way they felt. I wanted them to have the opportunity to express that. The more you think about these things, the more you realize that every place, every country, every culture, every value system is in a constant process of evolution. And so it becomes ridiculous in a way to judge things. And you start to realize it is much more important to see them the way they are at this particular moment in history. So I felt that it was more important to show a country in transition through women as opposed to a judgmental look at either worlds.

Where do you see The World Before Her heading? Do you plan to bring it to India?

There probably will be a limited theatrical release of the film, at least in Canada. There has been a lot of interest in the film, so fingers are crossed – very few documentaries get a great life, and if there is an interest in India, then even better. I’m also going to come back to India in May and then I’m going to personally sit with Prachi and watch the film with her family.

This article was originally published in Platform Magazine