The man who saved India’s sea turtles from extinction is the subject of a new documentary

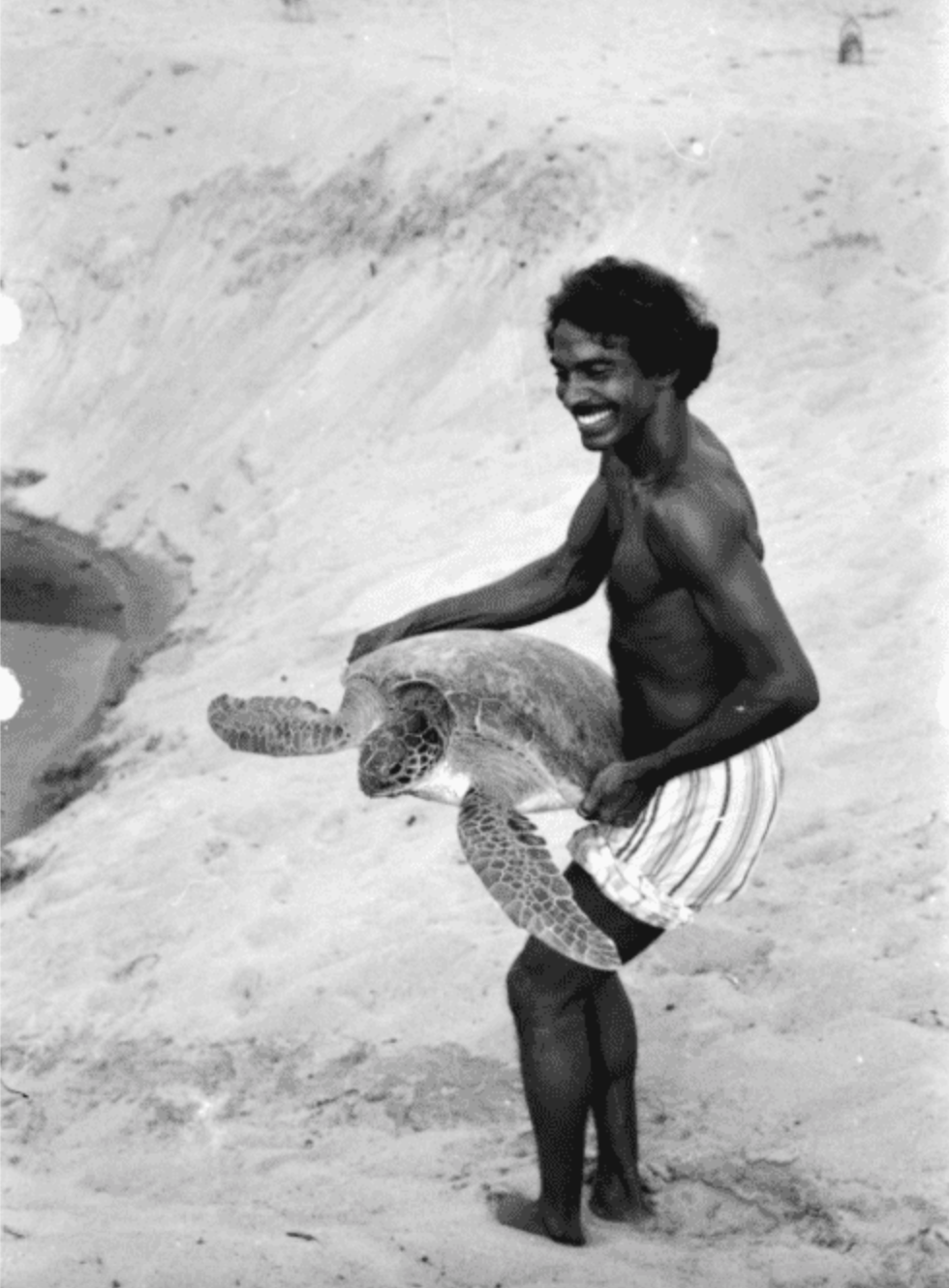

This story was originally published in The Nod. Cover image features Satish Bhaskar with a green turtle. Photographed by herpetologist Rom Whitaker at the Madras Croc Bank, circa 1979.

In 1982, a small-framed, lean man named Satish Bhaskar arrived on an uninhabited island in Lakshadweep. There were no maps, no cell phones, no human habitation—just an uninterrupted view of the cerulean, froth-lipped Arabian sea. His backpack carried a notebook, transistor, camera, snorkelling gear, basic medicines and food. For the next five months, Bhaskar would make Suheli Par—a lush green, oval coral atoll in the middle of nowhere—his home.

The modern-day Crusoe was on a mission: to carry out a survey of sea turtles that would record, in intimate detail, their identification and nesting sites. In the years to come, Bhaskar, who passed away in 2023, would travel over 4,000 km along the Indian coastline, conducting surveys by foot, discovering crucial nesting beaches. It is this work that makes him such a legend within the wildlife conservation community and an inspiration to generations of marine biologists.

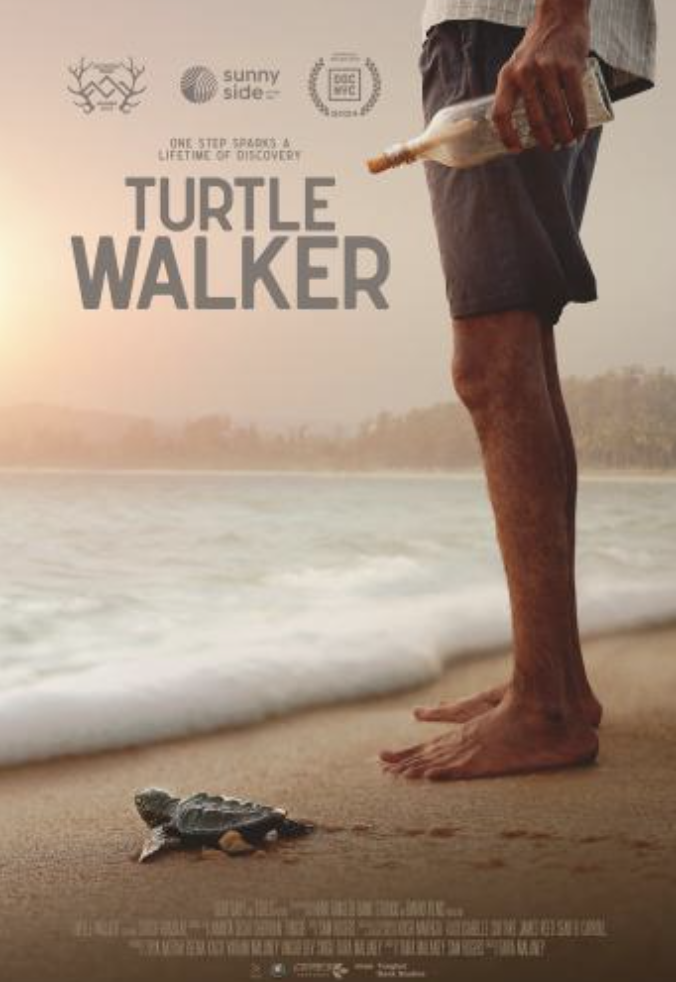

However, few people beyond these circles know much about his work. From almost single-handedly metal-tagging leatherback turtles in West Papua and trying to rescue hatchlings from predators to being chased by a wild elephant—Bhaskar’s life experiences are made for a movie. And now, a dramatised documentary on the veteran marine biologist will tell his extraordinary tale. Directed by Taira Malaney (with James Reed, the award-winning co-director of My Octopus Teacher as the executive producer), Turtle Walker takes its viewers on an adventure that retraces Bhaskar’s journey, and even examines the impact of the 2004 tsunami on sea turtle habitats. The film is backed by Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti’s Tiger Baby Films, as well as Academy Award-nominated HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, and premiered at Doc NYC 2024, New York in November and won the coveted Grand Teton Award in 2024.

It took Malaney a few visits to convince the self-effacing Bhaskar to agree to be filmed. “He shied away from the public and didn’t want to be the focus of attention,” explains Malaney, sharing that Bhaskar had no digital footprint either. “He took a long time to warm up. But once he started, he was so passionate about what he did that when we asked him about his work, he would talk non-stop.” Over seven years, Malaney and her team went on to record 26 hours’ worth footage on him alone, as he recounted his extensive process of collecting sea turtle data from 1977 to 1996. For Malaney, Bhaskar’s interview formed the “backbone of the film.”

Track and trace

While alone on Suheli Par, Bhaskar wrote at least 10 letters addressed to his wife, Brenda, which he would put into glass bottles and throw into the sea. One of these wandering bottles arrived in Sri Lanka and was discovered by a fisherman who posted the letter to Brenda in Goa. “The letter travelled 800km at least, and reached Sri Lanka in 26 days,” Bhaskar notes in the film. It was a strange kind of epistolary romance, made for the books.

It was on the island that he saw tracks made by female green sea turtles. From afar, the patterns resembled braided hair, which indicated that the beach was a well-visited nesting ground. However, “it was quite a few days before I saw my first green turtle laying eggs,” shares Bhaskar in the film. Finally, one day, he spotted the large marine creature not too far from his hut. The sea turtle was scooping and flipping sand with her spade-like flippers, and grunting sonorously. The labour-intensive burrowing was so she could lay a clutch of eggs. Such intimate experiences encouraged Bhaskar to make an ambitious commitment “to survey every single beach and every single island and every coast of every single island” in India. Suheli Par would become a pivotal part of his pioneering 19-year research-based journey.

A still from the film, ‘Turtle Walker’.

Walk, survey, report

It was in the 1970s that the then Chennai-based Bhaskar first approached renowned herpetologist Romulus Whitaker, with the intention of working with him at the Madras Snake Park. Whitaker had been conducting nocturnal sea turtle walks along the Madras coast all the way up to Kalpakkam; and his Snake Park wasn’t too far from IIT, where Bhaskar was an engineering student. “Satish was an oddball in many ways,” recalls Whitaker on the phone. He was “a very quiet fellow” and had “a natural inclination” towards sea turtles and the sea. “The turtles were magical to him.”

It was Whitaker who dubbed Bhaskar ‘Mr Sea Turtle’ and encouraged him to travel to Suheli Par. At the time in India, turtles were being ruthlessly exploited for their eggs and shells, and gutted for their meat. “I think they used to sell sea turtle eggs in Siddipet (a large market in Madras) for five or 10 paisa. But we didn’t know whether the turtles were endangered or not,” says Whitaker. So, when Bhaskar showed an interest in the slow-paced reptiles, “we just encouraged the hell out of him. It was a unique time because wildlife conservation and research were just emerging in India.”

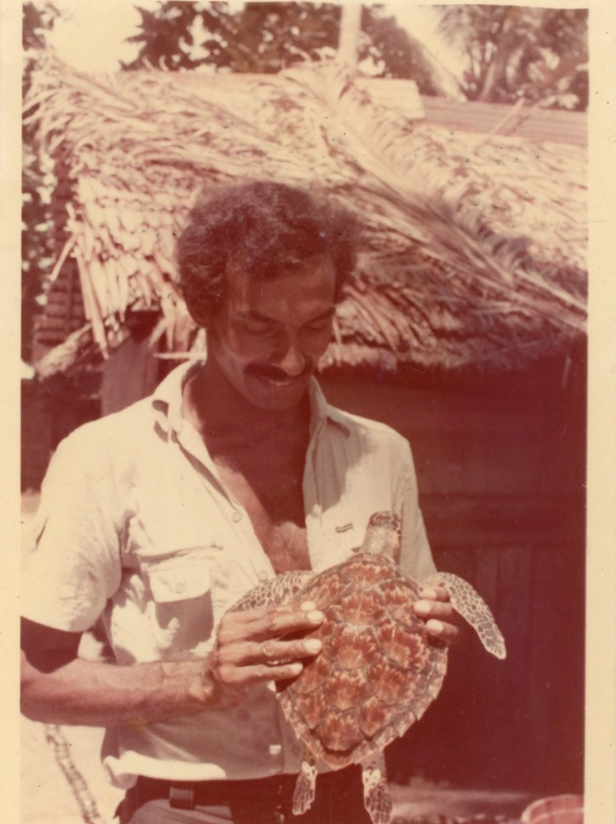

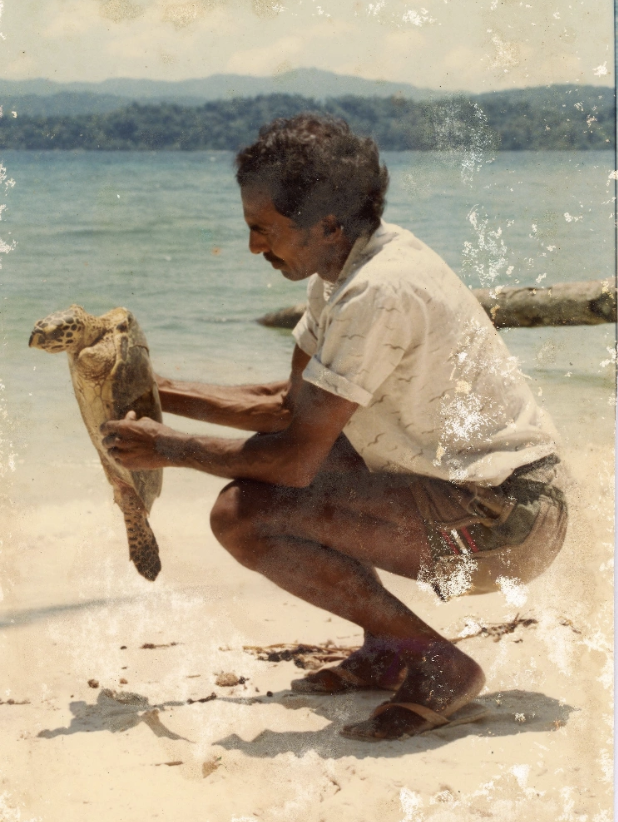

Satish Bhaskar. Copyright belongs to the Bhaskar family.

From determining the best hawksbill turtle nesting beaches in the Andamans, to discovering leatherback sea turtle eggs in the Nicobar, Bhaskar went on to cover two-thirds of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, among other coasts, on his own. During such expeditions, he sent letters to Whitaker and his team, detailing his experiences of being bitten by sand flies or cautiously watching a crocodile amble 10m from him.

Conserve, document, amplify

Turtle Walker is suffused with quiet, beautiful scenes. Whether discreetly documenting Olive Ridley turtles laying eggs or recording the hatching of baby turtles at night and watching them scurry away with their tiny flippers towards the vast ocean for their first swim—it is the stunning cinematography that invites the viewer into the world of these mysterious species. “For such scenes, our DoP, Krish, used infrared cameras for filming, so that the turtles wouldn’t get disturbed,” explains Malaney. In terms of research, shooting, and guidance, the team worked closely with the Dakshin Foundation, an organisation that focuses on marine-life conservation, led by ecologist Dr Kartik Shanker. It has been following in Bhaskar’s footsteps and astutely building on his existing work.

Sprinkled through the film are rare archival photographs, which Bhaskar painstakingly took during his professional trips. “He had this extensive archive of 300-400 scans that we developed to use in the film. Though I think there are probably many more,” says the filmmaker. Intrinsically reserved, Bhaskar wasn’t too forthcoming in terms of sharing notes from his journals at first. “Then one day, he got very excited,” continues Malaney. “I had asked him to fact-check something in his diary and tell us.” Bhaskar disappeared into his room and rummaged through the books. “Then he called me into the room and started reading his diary out to me.” Malaney was taken aback by how thorough his notes were. “He had recorded information like the day he weighed the heaviest leatherback turtle and other such interesting facts.”

Satish Bhaskar. Copyright belongs to the Bhaskar family.

From acquiring permissions to shoot on the protected beaches of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to almost having their boat capsize on one of the filming trips in Lakshadweep, it took the team an enormous effort to make Turtle Walker. But Malaney was sure she wanted to tell Bhaskar’s story, particularly at a time when sea turtles are marked by WWF as an endangered species. “We were very intentional that we wanted this film to be a story of adventure and discovery. Through Satish, we wanted the audience to experience [a sense of] wonder for the marine world, because I think that’s definitely a driving factor, especially for the youth, to engage in the conservation space.”

Indelible impact

The extraordinary measures Bhaskar took to protect these migratory ocean giants, at a time when it was completely overlooked in India, continues to deeply inspire those who’re committed to safeguarding the oceans and marine life today. “His surveys and sojourns on many uninhabited islands in Andaman, Nicobar and Lakshadweep provided the first (and in some cases, only) information on sea turtle nesting on these beaches…His published and unpublished reports have formed the basis for current sea turtle conservation initiatives,” writes Dr. Kartik Shanker in Indian Ocean Turtle Newsletter (Issue 12). The testimony is among many others that confirm Bhaskar’s reports have strongly impacted the marine conservation practises in the country and continue to do so.

For more details, visit here