Meet the eco-feminist army saving giant storks in Assam

This article was originally published in The Nod. Cover photo courtesy: Dr. Purnima Barman.

For the longest time in India, the greater adjutant stork has been regarded as a harbinger of misfortune and carrier of disease. This bald yet imposing scavenger bird (that wears its dark feathers like a cape), is almost 5ft tall and has a wingspan of 8ft. Its gait is military-like, which is how it got its English name. This omnivore has an idiosyncratic, reddish-orange neck pouch with an in-lit glow. In Assam, it’s known as ‘hargila’, which means ‘bone-swallower’.

Once found in large numbers across southeast Asia, today these oversized misfits are among the rarest species of birds in the world. In regions like Assam, you’ll find them foraging wetlands, scouring grasslands, and wading through landfills to survive. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, just about 1,300-1,500 hargilas are believed to exist globally, placing them in the ‘near threatened’ category. Since these giant birds have a distinct odour and feed on carcasses, bones, and offal, their presence is considered trouble. In the past, they have been victims of stone-pelting and nest-burning, and have even been poisoned. Loss of habitat, shrinking wetlands, and destruction of their nesting trees are also reasons for their dwindling numbers.

Now, a growing group of rural women in Assam is doing everything in its power to protect the greater adjutants from extinction. They call themselves the Hargila Army.

Stork sisters

In grasslands across Assam, clusters of indigenous women, draped in multicoloured saris and crowned with papier mâché headdresses resembling the head of a stork, dance in circles while singing traditional Assamese songs. It’s a striking sight. The smiling women, who belong to the Hargila Army, are purveyors of wisdom—educating village folks about the importance of these giant birds. (The headdress recently made its way to the Birds: Brilliant and Bizarre exhibition at the Natural History Museum, London).

The women arrive in large numbers, enthusiastically de-boarding buses and visiting new villages to cultivate positive perceptions of the hargilas among the locals. They knock on doors and encourage everyone, from village elders to children, to participate in the traditional Bihu dance, bringing out the taal (Assamese cymbal) and dhol. They clap their hands, and sing.

An all-women grassroots movement, the Hargila Army (made up of more than 10,000 volunteers) fiercely safeguards the birds’ nesting habitats, rescues fallen baby birds, participates in cleaning drives, and diligently plants kadam and shimul trees (preferred nesting perches for storks). Most of these women are homemakers who are given some coaching in conservation. Not only does the army track the hargilas’ behavioural patterns, which are drastically shifting due to climate change, but they also monitor their numbers, and map their nesting colonies via GPS tagging.

Hargila or the Greater Adjutant stork. Photo by Vijay Bedi. Courtesy: Dr. Purnima Barman.

At the helm is wildlife biologist Dr Purnima Barman, who single-handedly started the conservation project in 2007. Dr Barman says that over the years, there has been a steady and promising rise in the storks’ numbers: in 2007, about 400 hargilas soared across the skies of Assam, but “today, there are over 1,000 of them.”

It all started with a tree. About 17 years ago, in Assam’s Dadara village, a tall burflower (kadam) tree, home to nine greater adjutant nests, was razed to the ground by a local man. Dr Barman watched the tree collapse and the nests capsize. Amid the wreckage of feathers and twigs, were hapless wounded chicks—a few of which eventually died. As a mother of twin girls, Barman was heartbroken. “Watching them struggle deeply pained me. These poor baby birds could not speak or defend themselves. It felt like my own children were being persecuted,” she recalls. When Barman confronted the man, she faced fierce pushback from him and the other villagers. “They surrounded me, mocked and questioned me. They said, ‘The hargilas are a bad omen and are filthy.’ Right then, I made it my life’s mission to protect these birds and create awareness.”

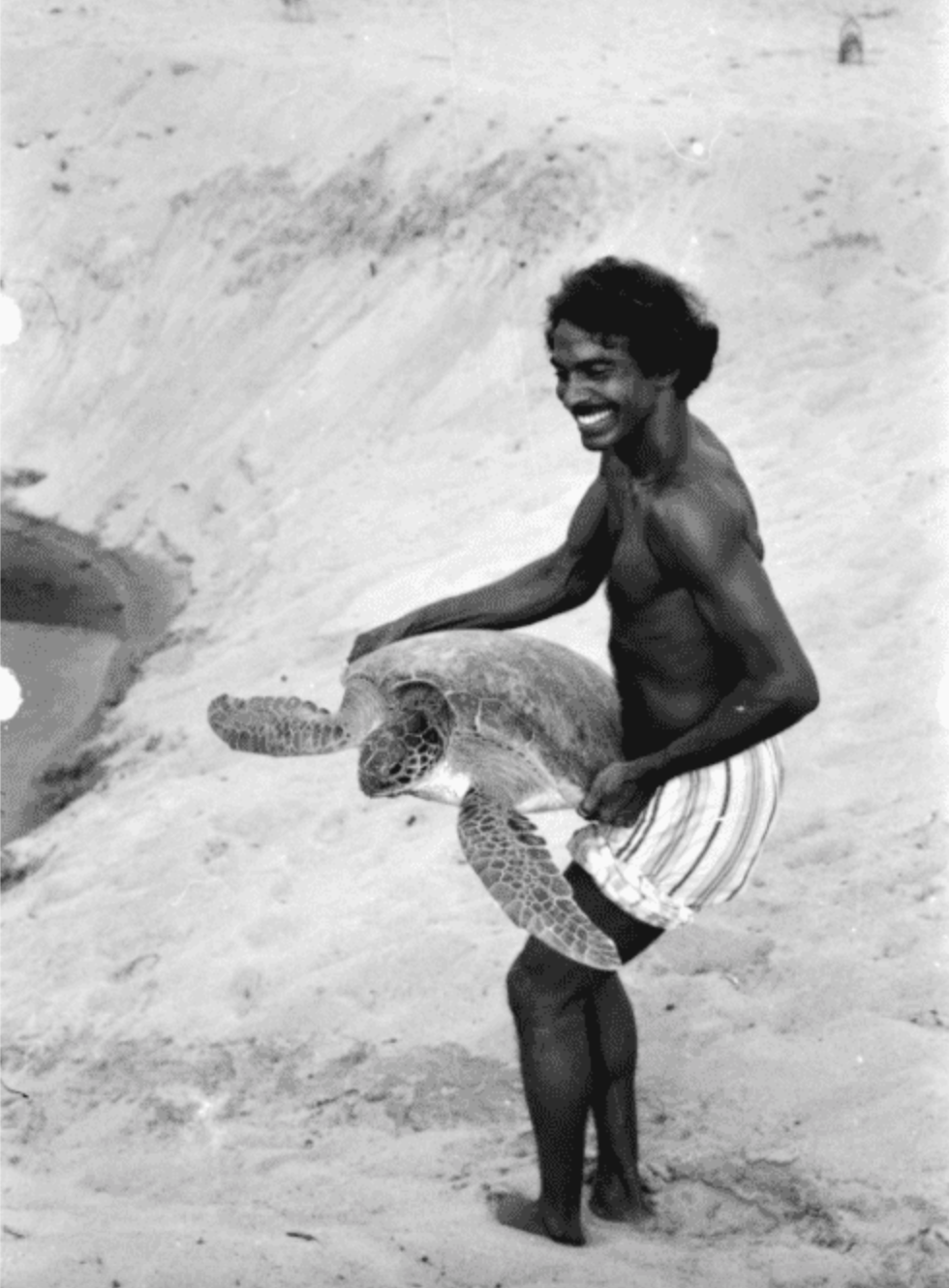

Dr. Barman rescuing a stork. Photo by Celia Pecchia. Courtesy: Dr. Purnima Barman.

The following day, Barman returned to the site.

The hargilas have a prominent smell, and sometimes, remnants from their scavenged meals plop onto the ground from the trees. Their fetid, watery droppings don’t make them great neighbours either. “Rather than fighting with the villagers, I decided to visit the man’s home and offer my services to help,” she says. Barman went on to clean the hargilas’ excreta, feathers, and other avian debris outside his home. To inculcate the respect for the hargilas in her daughters as well, she took them along to assist in the cleaning process.

Soon, the man became increasingly receptive to Barman’s cause. “I realised that there is power in changing people’s perception through one’s own actions,” Barman notes. “Earlier, I was telling the man what to do. But I realised that I had to show what’s possible.”

That gave her the boost she needed. “I visited other tree owners, fishermen and schools to spread awareness. I organised public meetings,” she says. “I also realised that more women needed to come forward to become a part of the solution, since they’re the educators in the family for their children.”

Initially, few were interested. The meetings had next to no sign-ups. Then, an idea struck. Barman began hosting pitha-laru (traditional sweets) making competitions, and “slowly, five, 10, 12 women joined.” Barman used this platform to have meaningful conversations about nature and how each being was interconnected. She nudged them to pledge to protect the environment and the hargilas. Over the next few years, Barman’s eco-feminist movement picked up momentum. “The Hargila Army began with 10 to 13 women, and now there are thousands of us working for the cause,” she says.

Women with hargila motifs as henna on their hands. Photo by Dipankar Das. Courtesy: Dr. Purnima Barman.

Green warriors

Barman’s work is now widely recognised. In 2024, she received the prestigious Whitley Gold award, and in 2017 was the recipient of Nari Shakti Puraskar awarded by the Government of India. As part of the conservation efforts, the women in the Hargila Army, weave greater adjutant motifs on the saris made from traditional red-and-white Assamese gamosa and mekhela chadors. These saris are sold, making the women financially independent. “The sari has become a strong tool for communication, environmental education, and female empowerment,” observes Barman. “Wherever our women go, they drape themselves in saris carrying the hargila symbols. People always ask about them; so, the saris are a good way of starting a dialogue around the storks.”

Such initiatives have meaningfully changed the women’s lives. They proudly travel to neighbouring villages to educate countless households about the storks. Take 35-year-old Karabi Das, who lives in Dadara village, and has been engaged with the group for the last five years. “I used to be at home doing household chores, looking after my husband and children,” she shares in Assamese. “But when I joined the Hargila Army, I learnt that women are not only meant for household chores. We can do something for our society and nature. We can also be economically independent like men. Now I am able to stand in front of a crowd and speak a few words with confidence.”

The ever-growing tribe of women comprising the Hargila Army. Courtesy: Dr. Purnima Barman.

Barman is passionate about transforming the stork’s identity from a monster to an endearing household name. And that change began with the women who joined the organisation. Pranita Medhi, 35 and a mother of three, joined the Hargila Army seven years ago. “Earlier, I only knew that the hargila was a large bird with a strong smell,” she says in Assamese. “After joining the movement, I learnt that it serves as a natural cleaner. These birds play a crucial role in waste management by feeding on decomposing organic matter, which helps prevent the spread of diseases. I now see them as guardians of our environment.”

Independent, smaller clusters of the Hargila Army are mushrooming on their own in various villages, which delights Barman. And recently, a new nesting colony has emerged in Kulhati village, populated by 52 nests, which means that the grassroots conservation efforts are yielding results. “In fact, we have been taking data of nesting colonies, and Kamrup district has the largest hargila breeding colony in the world, boasting at least 300 nests,” she says.

“When I started, I was told that only scientists are equipped to perform ‘conservation’ activities, or only they can protect endangered species,” says Barman. “But it actually takes community effort. The local people are the true scientists. Since their birth they have been co-existing with various species. Each of them holds traditional knowledge within them. All they need to do is try.”

Assamese interviews translated to English by Bashara Rani Das.