Master of Fine Arts

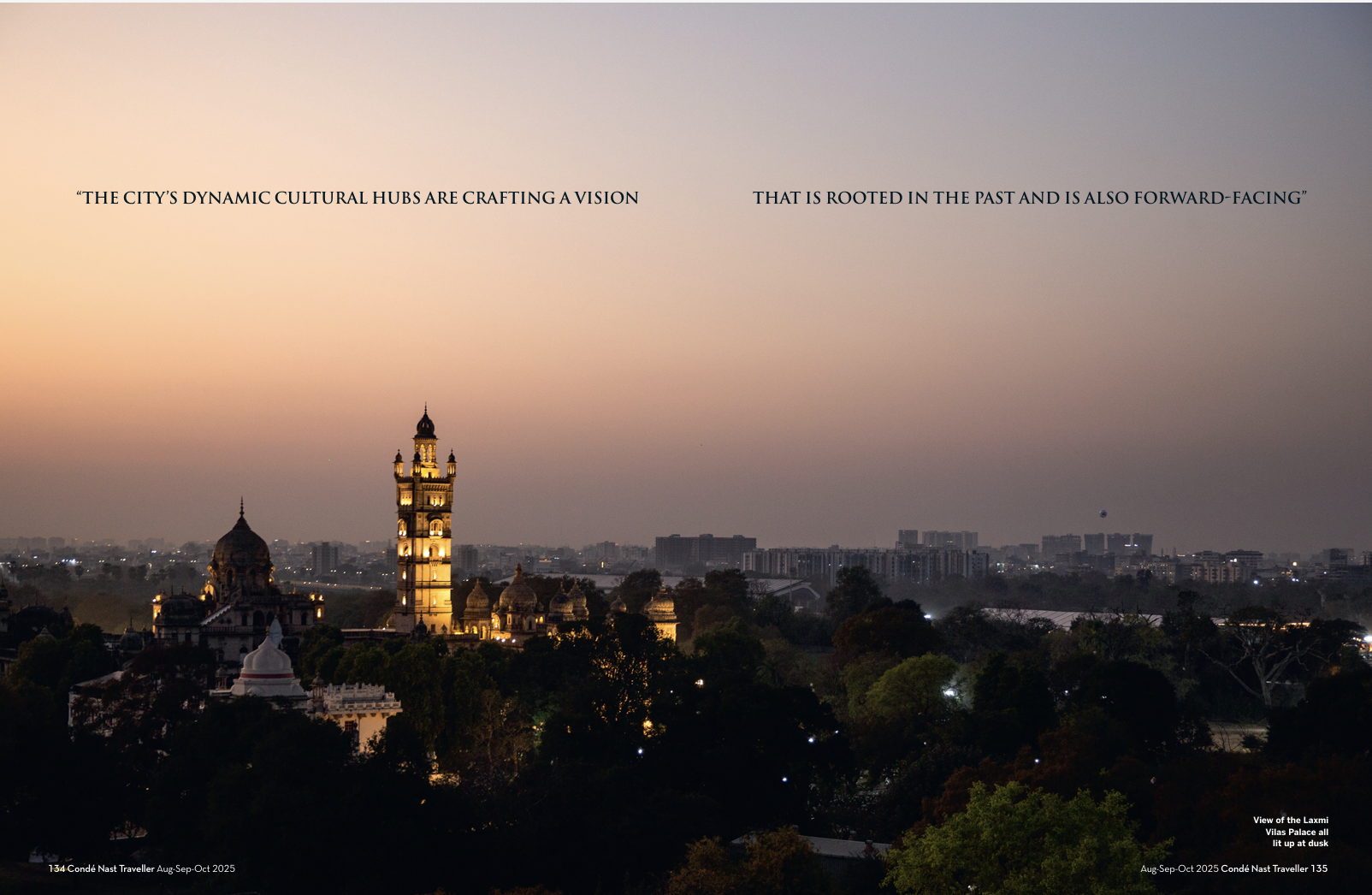

This article was originally published in Conde Nast Traveller India’s August 2025 issue. Cover image: Radhikaraje Gaekwad at Laxmi Vilas Palace, Vadodara. Photo by David Crookes And Nicola Jackson.

On a sunny morning, we find ourselves at Vidyadhar ni Vav—a 15th-century stepwell built in the memory of a saint—in Sevasi on the outskirts of Vadodara. When summer arrived, this ancient stepwell served not only as a water source but also as a communal space for rituals, and offered respite from the scorching heat. The vav’s aged bones are still formidable; its solemn walls muffle the city’s vehicular cacophony. As we descend the hewn stone steps into its darkening, sunken belly—layers of wispy grey smoke rise. Curious, we go further, passing a coterie of teenagers engrossed in taking photographs. A few landings below, we discover the smoke’s source: a sacred fire. In the depths of the step well lies a hidden shrine dedicated to Khodiyar Mata, a warrior goddess who wields a trident and rides a crocodile. We watch a woman circumambulating the holy fire. She bows her head before the deity, palms pressed together, her lips whisper a prayer.

We continue downward, observing the motifs of elephants and flowers etched into the pillars, half-erased by time. Though the stepwell’s water reservoir is no longer in use, it remains a popular spot for locals, especially for the younger crowd. Seated regally on one of the steps, a young influencer, in an emerald green sari and Maharashtrian jewellery, strikes a pose for the ’gram. It is a moment that captures the spirit of a city perched between the past, present, and future. Vadodara’s stories—of crocodiles sunbathing in the Vishwamitri River, cannons cast in solid gold, carpets embroidered with 1.5 million Basra pearls, or the erstwhile palace parrots adept at driving tiny silver vehicles for entertainment—offer a fleeting glimpse into the city’s fabled legacy.

Yet, most travellers visiting the state of Gujarat end up here on a detour from Ahmedabad or the 597-foot-high Statue of Unity, both about two hours away. We’re in Vadodara to learn more about the city as it was and as it is today. Our journey begins at the Laxmi Vilas Palace—a 19th-century palatial home and the largest private residence in India, belonging to the erstwhile royals of the city—the Gaekwads. We walk through its marble hallways, marked by scalloped arches with hand-carved motifs and sandstone columns. A stained-glass partition, which finds its provenance in 19th-century Belgian handicraft, is moved aside as we enter the Gaekwads’ private premises. We are directed to a courtyard, framed by lush ferns and towering palm trees. Tortoises crawl across the Minton-tiled flooring.

A close-up of an original painting by Raja Ravi Varma at Maharaja Fatesingh Museum. Photo by David Crookes And Nicola Jackson. Courtesy Conde Nast Traveller India.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the princely state of Baroda, under the Gaekwad dynasty, metamorphosed into a thriving centre of cultural affluence in western India, primarily through the vision of Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III. He invested heavily in the arts, architecture, libraries, and public gardens, which stood at par with the f inest in the nation. Laxmi Vilas Palace, constructed over a period of 12 years, is an example of his far-sighted artistic endeavours. At the courtyard’s centre stands an antique fountain, flanked by sculptures of Greek goddesses. This is the same courtyard where Maharani Chimnabai II, wife of Sayajirao Gaekwad III, would occasionally play the veena. “The women of the palace would use this courtyard,” says Radhikaraje Gaekwad, queen of the erstwhile kingdom and wife of Maharaja Samarjitsinh Gaekwad. “And the tortoises are the oldest residents of the palace.”

The Laxmi Vilas Palace, emblematic of enduring grandeur. Photo by David Crookes And Nicola Jackson. Courtesy Conde Nast Traveller India.

The Laxmi Vilas Palace, emblematic of enduring grandeur, reflects Indo-Saracenic architecture—a blend of Mughal, Rajput, and Gothic styles—featuring onion-shaped domes, open arcades, ornately carved jharokhas, sun-kissed courtyards, and expansive gardens. It still houses a fully functioning elevator that’s over a hundred years old. At the palace, Radhikaraje looks as though she has stepped out of a painting, as she elegantly arranges the folds of her chamois satin sari. As a new bride in 2002, she often lost her way in the maze-like corridors. Even today, she sometimes discovers a hidden carving—a relief of a monkey or an exquisitely detailed stone motif. “Living in the palace is an adventure,” she admits. “It’s like living in a museum.”

Nupur Dalmia, Director of Ark Foundation for the Arts; A dish at Bespoke Anna; Gazra café, Gujarat’s first LGBTQAI+ restaurant. Photos by David Crookes And Nicola Jackson. Courtesy Conde Nast Traveller India.

As one of India’s most respected textile connoisseurs, Radhikaraje helms the Craft Design Society Art Foundation, which is driven towards the resurgence of invaluable regional textile traditions. She tells me about a once-coveted, albeit rarely documented sari—the Baroda Shalu. This light, buttery tissue sari, once woven in Varanasi with real gold zari, was made exclusively for the maharanis of Vadodara. By the late 1960s, however, the Baroda Shalu had ebbed into oblivion. “Nobody seems to know much about it today,” says Radhikaraje, recalling how she first learned about the sari from her mother-in-law. “I was immediately drawn to the richness of the gold, the intricacy of the motifs, and the way it fell.” She’s now collaborating with karigars to revive the sari and bring it back into the limelight.

To read more, pick up Conde Nast Traveller India’s August 2025 issue. On stands now.