At 86, Arpita Singh continues to feel the urge to paint every day

This article was originally published in Vogue (Sept. 2023 issue)

For a considerable period of time in her career, Arpita Singh did not have a dedicated studio space. “At the time,” she says, “there was hardly any place to work”. It was only when her daughter left for school and her husband stepped out that she would wield her brush with sweeping strokes and paint for “long hours until they returned”. So perhaps it makes sense that the first thing the celebrated contemporary artist describes when I speak to her is her studio space, which holds ample natural light and a handful of her vivid artworks. It is where she goes every day to paint—a ritual that begins at nine in the morning and carries on till early afternoon.

‘Whater ever is Here…’, Oil on canvas. 2006. Credit: Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and the artist

Over six decades, the 86-year-old has built an oeuvre that continues to bewitch viewers. Singh’s paintings often have a surreal, fever-dream quality to them. The kind that appear otherworldly, yet resonate with the viewer on a deeper consciousness and seem eerily familiar. Take, for instance, If You Only Let Me (2022) from the Meeting series which was displayed at Frieze, No.9 Cork Street by Vadehra Art Gallery in June, marking the artist’s first solo exhibition in London. In the painting, across disjointed patches of emerald green, are empty park benches and solitary black figures that seem distorted as though they have been deliberately scratched out.

If You Only Let Me, 2022, Oil on canvas. Credit: Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and the artist

To some, the painting may evoke a sense of loss, a haunting loneliness; to others, it might convey chaos and confusion. Yet Singh doesn’t offer capsule explanations for any of her creations. She believes that art is open to interpretation and can’t be moored to one meaning. “All works of art, whether it is a book, a song or a painting, are mirrors,” she says. “In a way, the artist shows you the mirror and you see yourself in it.”

Broken phrases such as ‘If you only’ and ‘Change’ appearing as wistful skeins are scattered across the sombre landscape of If You Only Let Me. In many of Singh’s compositions, letters and words appear and disappear at will. Often, their presence seems jarring or incongruous, but they are almost autobiographical in intent; usually phrases plucked directly from literature or cinema that consume Singh during the period that she is making a particular painting. “Everything influences me. Whatever I read, whatever I do, all are connected to my art,” she explains. “In the evening, I generally read. If a line that I have come across interests me, I write it down in my work.” Maya Angelou’s famous poem once stirred something powerful within her, which prompted her to paint iterations of ‘Still I Rise’ (among other phrases) across her artwork titled The Tree (2020).

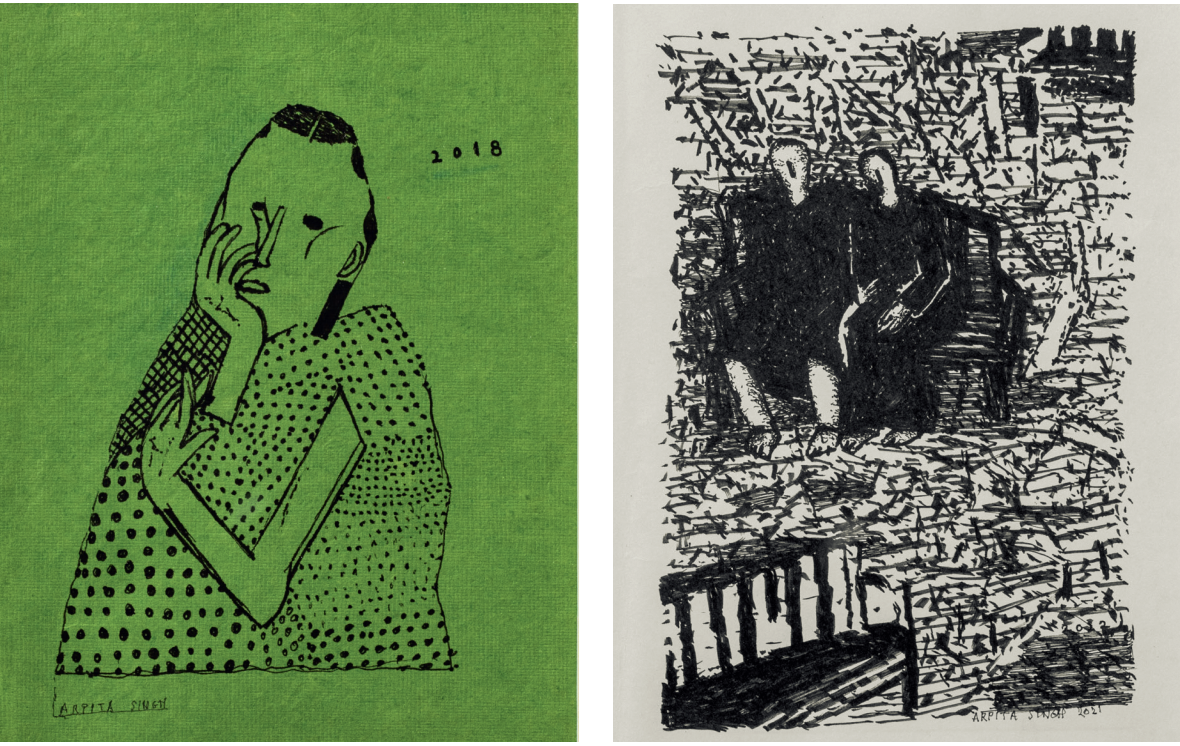

From left: Untitled (2018), Untitled (2021). Credit: Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and the artist

Our conversation is suffused with anecdotes. As a young artist, Singh could not afford sketchbooks. Thrifty and resourceful, she sketched on pages of used catalogues, newspapers and magazines. Tiny printed texts that may have bothered or stumped young artists—and in all probability would have prompted them to try and paint over the words—didn’t daunt Singh. In her compositions, texts visibly became a part of her creations. The octogenarian reveals this early experience as one of the reasons why words continue to inhabit her visual lexicon to this day.

My Lily Pond, Oil on canvas, 2009. Credit: Courtesy of Vadehra Art Gallery and the artist

In most of Singh’s paintings, large figures with compelling auras tend to dominate the foreground. The female protagonists, in particular, are seen holding revolvers, smoking cigarettes or posing naked with bouquets of flowers, their frail contours exposed. In the artist’s new series, Meeting, however, there is an evident shift. Human figures appear smaller and in proportion to their surroundings. The reason is simple: Arpita Singh no longer wants to make certain figures appear more prominent than others.

Singh’s complex (and at times, cryptic) artworks may leave the viewers flummoxed, yet these paintings, which seem to be an outpouring of her private fictions, are mesmerising. “Her work is able to engage audiences of all ages with its vibrancy, thoughtfulness and provocative imagery,” says Vadehra Art Gallery’s director, Roshini Vadehra. “Even with age, she has not lost her charm, wit or curiosity in the way that she approaches paintings—her strokes and characters continue to evoke emotions with a strong narrative in each work.”

When Singh and I speak, the Frieze exhibition in London has just concluded and she is already onto her next project. The new exhibition will open at Milton Keynes Gallery in the UK in October. “I must work every day,” she confesses. “It is an urge from my body.”