For Indian teen who launched village library, it’s about more than books

This article was originally published in Christian Science Monitor. Cover photo courtesy: Nawaz Rahman and Akbar Siddique

It’s 6 in the evening, and Sadiya Riyaz Shaikh is carefully painting the leaves of a tree on the powder-blue walls of a small room. Young visitors huddle around the 18-year-old, giggling shyly while advising her on colors. She writes the English alphabet and the numbers 1 through 10 along the branches. Outside, dusk has settled. In the glow of a tube light, a few older children quietly read their books in a corner.

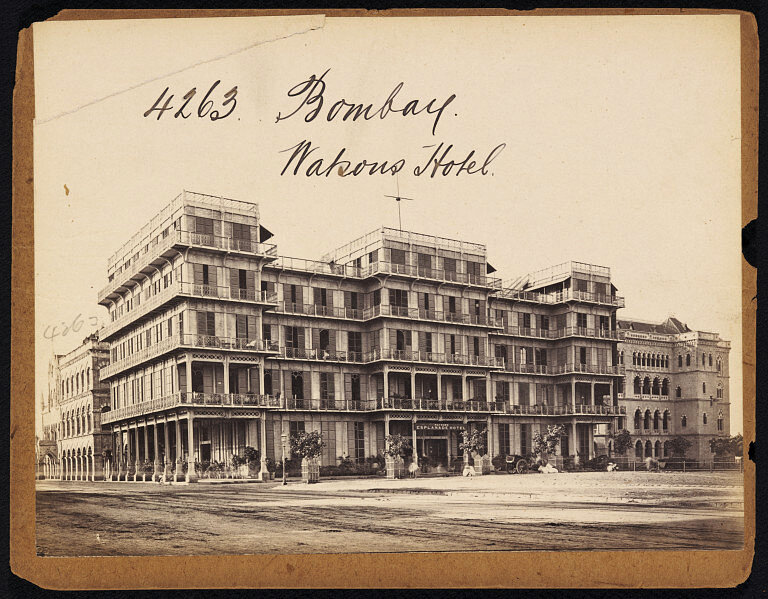

This is no ordinary place. Here in Deora, a small village in Bihar, a state in eastern India, it’s the only library. Standing at the edge of a road, the unassuming Maulana Azad Library can easily be overlooked, unless you stop to read the bright yellow board bearing its name. Just a few months ago, it was a dilapidated guesthouse. But when Ms. Shaikh came back to her ancestral village to wait out the pandemic, she had an idea.

Child marriage is common in Deora, she noticed, and attending school is not. The village of 3,500 has a male literacy rate of 45%, while the female rate is 38%, according to the last census. “Many families often withdraw their children from schools because they cannot afford to buy books for the prescribed syllabus or even uniforms,” Ms. Shaikh says over the phone. Some families don’t wish to educate daughters, she adds, and other children are forced to work in the fields with parents and siblings.

She herself was born here, but moved to Mumbai when she was 3 years old. Amid the pandemic, her father’s small manufacturing business had to temporarily shut shop, and the family was forced to return. Since September, she’s transformed the small space to provide schoolchildren with access to books they otherwise could not afford, and a supportive place to study.

It’s one of many times Ms. Shaikh has tried to use her own opportunities to open doors for others. A polyglot in Hindi, Urdu, and English, she often speaks at inter-college events on the right to education, women’s empowerment, and unemployment. For as long as she can remember, she’s loved standing in the midst of a spellbound audience. Last year, amid nationwide demonstrations against a contentious citizenship law accused of discriminating against Muslims, she took to the stage to speak out against rising intolerance and the police crackdown on student protesters.

“Our culture dictates that girls should remain in purdah and they needn’t attend schools or colleges. But I see things differently. I know that girls are capable of doing great things just like boys, as long as they are respectful towards their parents and others. So, I don’t care about what the villagers think of me. I won’t let that stop my daughter.”

Getting to work

This July, back in Deora, Ms. Shaikh sat down with her family elders and proposed the idea of the library. Many shook their heads in disagreement – this wasn’t how a young girl should spend her time.

After many discussions, she finally convinced them, and gained access to her relatives’ guesthouse, renovating it with almost 5,000 rupees ($67) she’d won in public-speaking awards over the last two years. She took the help of her uncle, Akbar Siddique, and cousin, Nawaz Rahman, and got to work. Walls were repainted, the bamboo roof was repaired and fastened to a crimson tarpaulin, lights and a bookshelf were installed, and the room was filled with plastic chairs and a table. Vivid charts tacked to the walls – from anatomy and transportation, to India’s “freedom fighters” for independence – enlivened the space.

The 7-by-12-foot room was ready for big dreams.

Named after India’s first education minister, the Maulana Azad Library houses hundreds of new and secondhand school books (acquired through donations and fundraising). Coloring and story books are provided to younger children. Ms. Shaikh also managed to secure subscriptions to Hindi and Urdu newspapers. Not all the books are in great shape – some are dog-eared or slightly frayed. But for some readers, they are crown jewels.

“If I continue to listen to others, I’ll never be able to achieve anything. The only way I can prove anything to anyone is to let them keep talking, while I keep working.”

Local schools often lack support, with sparse furniture and lighting. Deora’s students sit on thin floor mats. Those who really want to learn, like 14-year-old Ayaz Rahman, have to find alternatives. After-school tutoring can cost 500 rupees a month ($7), a huge investment for families like Ayaz’s. “I don’t have money for coaching classes,” he says bluntly. Ayaz lost his father a few years ago, which put his family under financial stress. His older brother, who works as a foreman, is the only earning member in the family of nine.

The library serves as a refuge that whisks him away every day, where he spends at least an hour studying or reading the Hindi newspaper. Using “book guides” that support his textbooks, “I’ve been able to cover my entire ninth grade syllabus,” he says. “Without the library, I wouldn’t have been able to manage it.” A tutor is paid to look after the space, and assist children with texts, alongside two young volunteers.

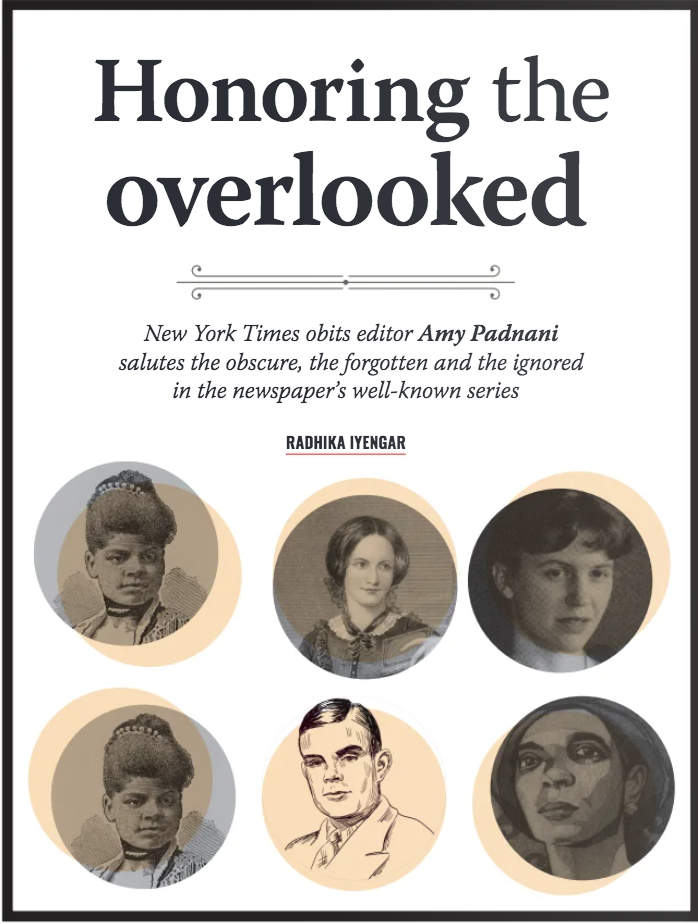

Sadiya Riyaz Shaikh reads in the Maulana Azad Library, which she founded and decorated. She used her own prize money from speaking competitions, as well as donations, to collect hundreds of books for the library.

“Let them keep talking”

Before the library opened, a few neighbors turned naysayers. Some, with great delight, prophesied that things would soon go south. But “if I continue to listen to others, I’ll never be able to achieve anything,” says Ms. Shaikh, her oval face framed by a gray hijab. “The only way I can prove anything to anyone is to let them keep talking, while I keep working.”

Her strongest ally is her father, Reyaz Ahmed Shaikh. Mr. Ahmed Shaikh recalls how certain villagers began looking at him “differently” once his daughter began undermining village expectations. “I think they’d prefer if my girl stayed at home and did not venture out in public,” he says. “Our culture dictates that girls should remain in purdah and they needn’t attend schools or colleges. But I see things differently. I know that girls are capable of doing great things just like boys, as long as they are respectful towards their parents and others. So, I don’t care about what the villagers think of me. I won’t let that stop my daughter.”

Ms. Shaikh is acutely aware of her privilege. The goal is to use it to rally one youngster after another, in hopes that they can alter the village’s trajectory. “These children have an intelligent mind. I’ve seen that,” she says.

Recently, she’s returned to Mumbai, but gets daily updates on the library from her cousin. In her eyes, the project is just beginning. Ms. Shaikh is working to organize scholarships for Deora’s children, and hopes to gather a group of volunteers to start libraries in neighboring villages as well.

Deora – like much of India – has been a ground for Hindu-Muslim discord. For now, only Muslim children are visiting the library, Ms. Shaikh says, but that’s something she wants to change. “It may be that non-Muslims fear they are not welcome in our library, but we want to eradicate such fears,” she says. “Books do not discriminate against who is reading them, so everyone is entitled to them.”

“I think the gap between Muslims and non-Muslims can only be repaired through education,” she adds. “If we want to change society, we have to take everyone with us in our progress.”