India’s Vibrant and Idiosyncratic Truck Art

This article was originally published in Hyperallergic. Cover image: A truck artist, Raj Dongre painting the “nazar battu” to keep the evil energies away; Photo by Manjot Singh Sodhi. All images courtesy: All India Permit.

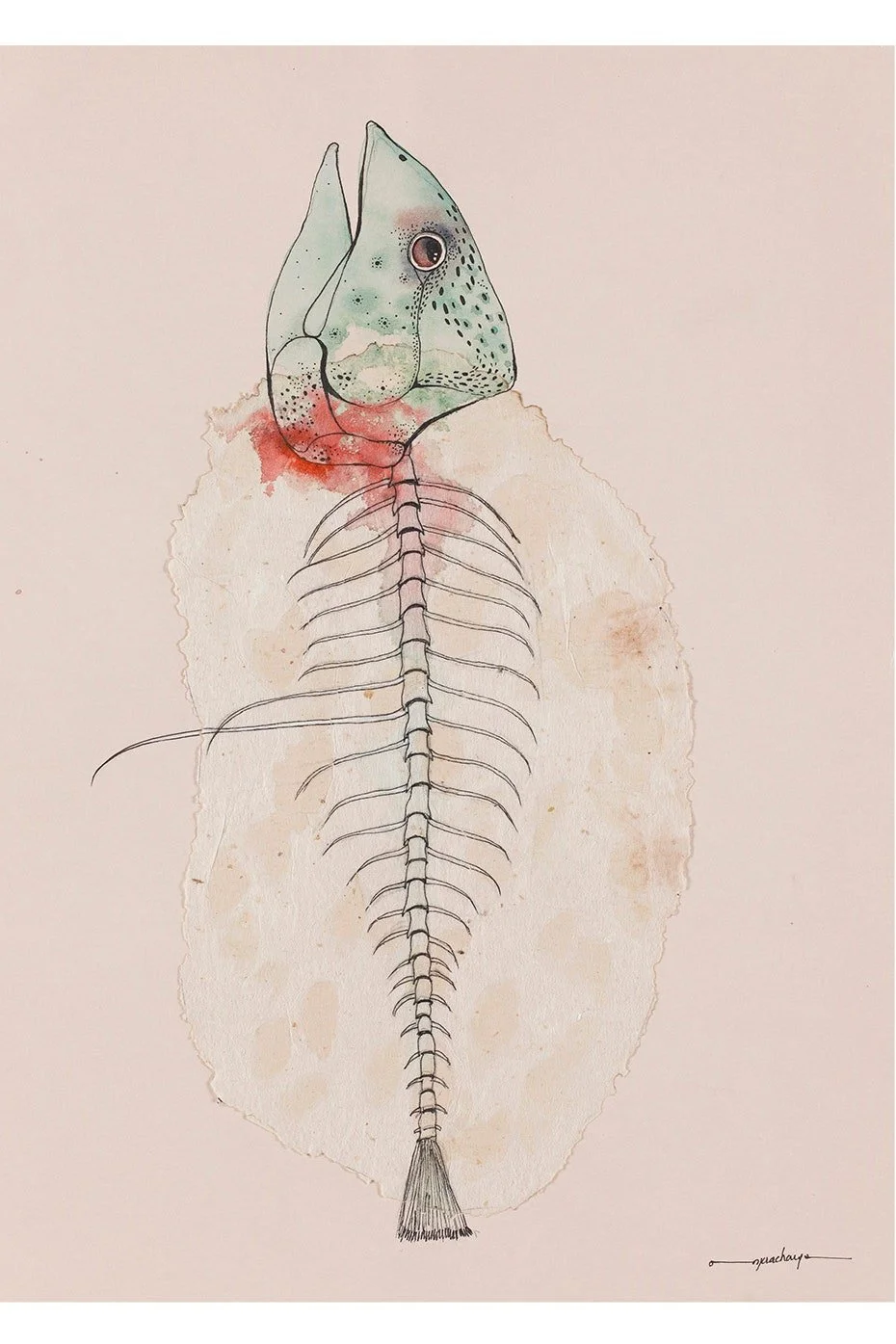

An apsara dances in a diaphanous skirt, small yellow daffodils blossom, a menagerie of tigers and elephants roam in the midst of wing-flapping birds — all of these come to life together on the steel panels of India’s trucks. Hand-painted symbols, elaborate patterns, and quirky slogans with bold typography coalesce into vibrant, idiosyncratic artworks. Truck art has been a part of India’s visual lexicon and heritage for decades. Highways transform into runways for chunky vehicles drenched in hues of tangerine, canary, plum, and jade green.

A truck artist with his paint cans. The artists work without gloves and use turpentine to remove paint from their hands. (photo by Ishika Aggarwal).

In India, trucks play a pivotal role in transporting heavy-duty goods, journeying for endless kilometers across the country. Most drivers are on the road for weeks, sometimes months at a stretch, living a nomadic life and often sleeping and eating in their vehicles. Their trucks become their travel companions and their homes, and the drivers go to great lengths to beautify them. They work closely with truck artists, describing the illustrations they would like to see.

“A good artist should have a steady hand and an intuitive understanding of color-pairing,” said Raj Dongre, in Hindi, over the phone. He has been embellishing trucks with his designs for over three decades. Before the country was engulfed by the pandemic, he worked in a truck-building workshop in Nagpur. In the summer heat, wearing scruffy clothes, he would dip his brush in colors of indigo and green, and glide it across the truck’s sturdy body, defining the fine feather wisps of a peacock. His hands moved with adept flourish, while songs from old Bollywood films played on his mobile phone.

“Blow Horn” is a common phrase painted on trucks. (photo by Manjot Singh Sodhi)

From golden-crested eagles to ruby-lipped roses, he has drawn them all. The handiwork on the truck — from the crown to the number-plate — is a patchwork of the truckers’ emotions, aspirations, faiths, and cultural roots. “One of the common motifs painted on trucks is a white cow nuzzling its calf,” explained Dongre. “It reflects the driver’s yearning for his mother while he is on the road, or the understanding that he will always be protected by her. The eagle represents speed, but also the feeling that no matter how far it flies, its eye will always be towards its home.”

A superstitious totem often seen on the bumpers is the nazar battu: the mug of a sharp-toothed demon with matted hair, believed to ward off the evil eye. Graffitied catchphrases like “Horn OK Please” and “Use Dipper at Night” (the latter encourages other drivers to dim their headlights at dusk) are now an inextricable part of the truck nomenclature.

A trucker’s love for his country, “India is Great” (photo by Farid Bawa)

The graceful art form had an unlikely beginning. Cargo trucks predominantly began plying Indian roads during the World Wars. Deployed as armory vehicles, they sported a mean camouflage look. “After the Second World War, however, the trucks were made available to the public for transportation of goods and passengers,” explained Farid Bawa over the phone, an Indian designer based in the Netherlands who collaborates with truck drivers back home. Bawa’s family is deeply rooted in the truck business: he grew up watching over a dozen skilled artists at his family-owned truck yard. “Anecdotally, it’s said that because the vehicles looked scary, not many people wanted to sit in them,” he shared. So, the local artists stepped up with their bright paint cans and gave them their campy avatar.

Over the last six years or so, however, he has noticed a precipitous dip in the art form. With the arrival of pre-painted trucks and radium stickers, homegrown artists from small towns and villages whose livelihoods depend on it are being forced to find work elsewhere.

“Hand-art is getting neglected,” said truck artist Akhlaq Ahmad, who has been in the field for the last 20 years. “Many drivers prefer pasting radium stickers all over their trucks, because it’s new.” The adhesive-backed pictograms are cheap, and the truckers save time by slapping them on, rather than waiting three to four days for the paint to dry. Ahmad frowns upon the stickers, noting that “with hand-drawn art, each truck driver can tell his story. In comparison, the radium stickers are all alike and don’t offer any kind of uniqueness.”

A freshly painted truck at a truck yard called “Bunty & Anand Body Works” in Nagpur, India (photo by Manjot Singh Sodhi)

To preserve and promote the country’s ephemeral art tradition, Bawa launched All India Permit (AIP) in 2018, an art project which collaborates with local truck artists. AIP supplies them with Cold Rolled steel sheets on which they paint their vibrant creations. In turn, these pieces become one-of-a-kind collectors’ items, available for sale. A sizable portion of the proceeds goes to the artists, providing them with financial sustenance, particularly during the ongoing quarantine period. AIP’s online platform showcases the artworks, while educating visitors of the art form’s cultural relevance.

“Unfortunately, I think this might be the last generation of truck artists,” speculated Bawa. “Many want their children to work in air-conditioned offices, not on rough highways. Also, there is [financial] uncertainty in this field.” While both Ahmad and Dongre don’t want their kids to inherit their profession, they believe that truck art will never peter out. “Otherwise,” Dongre mused, “the Indian highways will be gloomy and bare forever.”